|

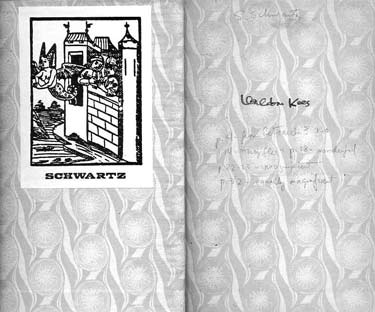

Ex-Libris Weldon Kees

It took me many years of trial and error to finally

have this mental filmstrip of Weldon Kees on his

lunch hour, browsing the shelves of the Holiday

Bookshop, which used to be at 49 E. 49th

Street. He could easily walk there from Paramount's

newsreel studio on W. 43rd Street, where

he worked as a scriptwriter. The bookstore was in the

vicinity of his favorite restaurants, such as Diamond

Jim's at 42nd and Broadway, where he ordered pot

roast and potato pancakes. He also liked Marnell's on

East 47th Street and some of the restaurants between

7th and 8th Avenues on 45th Street. The Hapsburg

House, Ludwig Bemelmans' caf�, had murals of the

little girls from his Madeline stories for children.

There, Kees, author of the poem "For My

Daughter," in which he at once expressed a

longing for and revulsion from a daughter of his own,

could enjoy the irony of his presence in such a

setting. He also found enchanting the restaurant's

lesbian clientele, which included Marlene Dietrich

and Greta Garbo.

This neighborhood also afforded Kees the chance to

run into old friends from his days at Time—or

the New York intellectuals who befriended him when he

first arrived in the city in the winter of 1943, a

former Denver librarian and a promising young writer

who seemingly had published in all the avant-garde

magazines. Once he came up behind Edmund

Wilson on the corner of Sixth Avenue and 45th Street.

Even though they had not seen each other in some

time, they quickly dispensed with warming up to each

other and fell into a conversation about the

"shocking and dreadful" new Lionel Trilling

novel,

The Middle of the Journey,

with the character based on Kees's old boss at Time,

Whittaker Chambers. So many of Kees's encounters

were like that in the '40s—the decade—and

in the Forties—that part of uptown. One could go

for years without seeing a friend and then there he

or she was on the sidewalk. And one took up where

they had left off. It made Kees feel at once

estranged and part of the city, too, like his alter

ego Robinson, the man with "the heart dry as a

winter leaf," who had already made the first of

his three appearances in The New Yorker—the

magazine where Wilson worked.

On the same day he encountered Edmund Wilson, I

can imagine Kees entering the Holiday Bookshop. His

eye would have fallen on art books. (He painted

abstractions and would succeed his friend Clement

Greenberg as The Nation's art critic.) It

would have fallen on books about music theory and

music history. (He lectured on these subjects at the

Abstract Expressionists' "school" in the

Lower East Side.) And he would have looked out for

his friends' new books—Howard Nemerov had just

published his first book of poems The Image

and the Law—and taken a kind of

inventory of books by his new publisher, Reynal &

Hitchcock: Malcolm Lowry's

Under the Volcano

and his first trade book of poems, The Fall

of the Magicians. Certainly Kees saw

a stack of

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century, a new title in the

foreknowingly if democratically named Everyman's

Library series. I know he purchased a copy

because I, his biographer, now own it.

His book, my book, came from Jim Carroll's bookstore in San

Francisco, the city where Kees lived until 1955. By then he had

amassed a rather large library of books, many of them first editions

and entire runs of the little magazines in which he published such

as Furioso and The Tiger's Eye. This collection Kees

began during his college years in Lincoln, Nebraska. It grew as he

moved from city to city: Chicago, Hollywood, Denver, New York,

Provincetown, and finally San Francisco. He kept his books in

meticulous order, even when he had to make do with nothing but

bricks and boards for shelves. When he lived on Dana Street in

Berkeley, he had at last found a home in which he had built-in

bookcases in the living room. I have a photograph of his wife Ann

Kees wearing black slacks and a matching mock turtleneck, sitting

with a wall of books behind her, as much a stylish object as the

books were in the well-ordered life of poet husband. And my book,

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century, might even be in that photograph, too,

shelved perhaps near where Ann Kees's hands rest on one of the lower

shelves, where, I am sure, Kees would have alphabetized the book

under the name of the anthology's first poet, Sir Thomas Wyatt.

This photograph was taken during a happier time, in 1952. Two

years later, Ann's alcoholism resulted in her institutionalization

and a broken marriage. And

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century would have been put in a box by Kees in September

1954 and probably never put back up on a shelf, for he lived

tenuously in cramped apartments for the next ten months.

On July 18, 1955, Weldon Kees parked his car on the Marin County

side of the Golden Gate Bridge and has not been seen since. Taking

over his son's affairs in the weeks after the disappearance, John

Kees, a retired hardware manufacturer, entrusted the books to one of

Weldon's friends for safekeeping should Weldon ever return. The

arrangement John made with Weldon's property were more to comfort

his mother Sarah than it was for their son to take up his life where

he had left off.

|

|

Ann Kees and her husband's books, Berkeley,

1952. |

But Weldon did not reappear from Mexico or Hawaii or Australia�or

even Los Angeles�all places his friends thought he might have gone

to start up a new life. In late 1956, the elder Kees gave

instructions for the sale of the books to Kees's friend, Walter

McGrail, a former silent film actor Kees had befriended and now the

owner of the Old Book Shop on Sutter Street. McGrail and his sister

Miriam had appraised Kees's books in his apartment before John had

the movers come to empty it. They had hoped to receive Kees's entire

collection, including an entire shelf of Henry Miller first

editions, a copy of

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,

which had been signed by Kees's friend, James Agee. There were also

first editions of Gertrude Stein, Lorca, Eliot, Kenneth Rexroth,

Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Max Beerbohm, and Virginia

Woolf. These books and others�Kees's copy of Nemerov's first book of

poems, his copy of

Under the Volcano,

which he read again on a train to San Antonio in 1950�had been

promised not only to the McGrails but to a number of Kees's friends

who wished to have something to remember him.

The most valuable books from the collection, however, were not

inside the cartons that finally shipped to the McGrails. ("The

number of missing books is rather startling," Miriam McGrail

complained to the sender, who claimed the books had actually either

been his or had been borrowed and not returned.) Nevertheless, a

considerable number of Kees's books were sold from the Old Book

Shop, and for many years it was fairly easy to find one of them in

the stalls of San Francisco many secondhand bookstores.

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century is signed in ink on the flyleaf by Weldon Kees. He

put his name in all his books this way. Though he liked having

personalized stationery printed and the like, he did not have a

bookplate made. There is a bookplate in Kees's copy of

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century, and it did not take long for me to buy into

thinking that it's Horace Schwartz's, the late San Francisco

literary agent. Schwartz, like Kees, was originally from Nebraska

and befriended the poet in January 1955. Schwartz had once played

tympani for the Cleveland Symphony and had conducted one of Harry

Partch's percussion ensembles, which more than qualified him for the

drum roll that opened Kees's show, "The Poets Follies of 1955," at

which the San Francisco strippers Lily Ayers and Rikki Corvette read

Sarah Teasdale and T. S. Eliot in addition to the other bohemian

entertainments that Kees directed. The flyleaf of

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century also bears the thin, mechanical pencil signature of

Horace Schwartz's son, Stephen. So I connect dots, I line M&Ms of

maybes in my favorite colors, for biography begins with something

like play, like first-grade homework, for how else could it hook you

for a lifetime? I start seeing this book as devolving to the younger

Schwartz via the elder�who may have been one of those friends who

made a kind of everyman's library of Kees's books.

I had more to go on than just the book, too. I had received a

letter from Horace in 1984. He had responded to an author's query in

The New York Times Review of Books, and I wrote him back with a

battery of questions, which were designed to help the memory and

elicit responses from Kees's friends, but also ran the risk of

making me sound too well-informed about my subject, to the point

where it sometimes overwhelmed my recipients. This unintended effect

must have been played out on Horace, for he did not have much to say

and his memories seemed to touch on more than just Kees's wrongs:

Weldon (after his N.Y. life) was a broken, ill, neurotic man. He

took large doses of medicine for various illnesses.�Weldon remained

a New Yorker, displaced Nebraskan very like James Agee.

Time-Life and the Nation had scared him for life.

Weldon was a brilliant, sad poet of the Yeats type�introspective,

beaten, provincial. He could portray American reality with the same

acid truth as Wallace Stevens. But America has no place for a Weldon

Kees.� Weldon was a very beautiful man, of exquisite sense and

feeling.

Horace did, however, enclose a typescript of his son's poem

"Homage to Sir Thomas Wyatt" as a kind of rain check for not being

able to perform for all my questions. I could only remember that I

had read the poem without much good will, for such unsolicited gifts

that seemed beside the point were as welcome as getting only clothes

for Christmas. I wanted Kees's dots, my biographer's candy. But

after I had dug Horace's letter and his son's poem out of a box of

files, I found that I had already met up with

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century

before the Bookfinders search engine did:

Your book came to me, my friend, from the other world�

A copy owned by my father's friend, Weldon Kees;

Another poet, an early suicide;

I was a child of eight years when he died.

Beneath Kees's signature are penciled notes listing page numbers

and brief comments such as "wonderful" and "magnificent." These

superlatives intrigue me, for Kees had a style for dispraise, but

not one for praise. I turned to the first of these poems, a Wyatt

sonnet, on the lark that I might see some rare passion from, not

just shown for some jazz in his record collection. (One of many

compartmentalizations in which he retreated in his last years from

the disappointment of being an American poet.) Perhaps seeing him

warm to some lines of poetry would have an afterglow. After

finishing a book about him, after thinking about him so much, I had

as much on paper as Rilke had an archaic torso and what could be

imagined. But there were many more cold, lunar pieces than this

effusion over an Elizabethan that even he knew would be there. After

all, he had said himself�foreshadowing my own endeavor�sketching out

an unwritten novel in 1944 about a poet-cipher and his biographer:

The task of fully discovering and understanding another human

being�at least this one�is an impossibility.

Yet reading the words, the lines, the passages underlined in a

book by another hand is like following a person up a deserted

street. They are ahead of you. There is no one else. Kees understood

that you can be picked up by the undertow of such an experience in

one of his poems:

Somewhere in Chelsea, early summer;

And, walking in the twilight toward the docks,

I thought I made out Robinson ahead of me.

From an uncurtained second-story room, a radio

Was playing There's a Small Hotel; a kite

Twisted above dark rooftops and slow drifting birds.

We were alone there, he and I,

Inhabiting the empty street.

("Relating to Robinson")

This strange impression of following someone is all the more keen

as I opened

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century. There are only a few lines underlined, only

a few poems framed in pencil. I would think if the book were marked

up more intensely, the strange impression would be drained. Here, in

this book, it seems that only the most essential lines have been

identified, the lines that contain the only things that mattered

to the reader. In the editor's introduction, Wyatt's "blend of

haunting cadence with direct personal utterance" flows into this

underlined passage:

show clearly and unmistakably the influence of the English

song-books then so much in fashion.

My first response is to suspend all doubt and relate this to Kees

and no one else. He would have read this remark first in this

book and, I think, would have savored it. He used the

popular music of his own time in his poems. Certainly, he would have

at least paused over this sentence long enough to feel some kinship,

some parallel. Perhaps he felt for a moment that he would be

remembered this way, years from the day he bought the book at the

Holiday Book Shop and, perhaps, saw copies of his book going unsold,

that he might be a silver poet of the 1940s�silver being a way "to

distinguish without disparagement" the minor poets of three

centuries ago.

I turn to the flyleaf. Page 4 is the first notation, with the

comment, "from Petrarch? No." This takes me to one of Wyatt's

sonnets completely set off in penciled brackets. The lines jumped

out:

I find no peace, and all of my war is done,

I fear, and hope. I burn, and freeze like ice.

I fly above the wind, yet can I not arise.

And naught I have, and all the world I season.

That loseth nor locketh holdeth me in prison,

And holdeth me not, yet can I scape nowise:

Nor letteth me live nor die at my devise,

And yet of death it giveth me occasion.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I desire to perish, and yet I ask health

These lines suggest so much of Kees' struggle to be at once free

and involved. I can see the man who wrote poems about how a room the

size of Nebraska and rooms the size of small, New York apartments

closed in just as much on you. I can see the irascible painter who

helped in the effort to get all of his Abstract Expressionist

friends into Life magazine and then wanted nothing

more to do with them�and fame. I see the man in 1951 who, in utter

despair over the rejection of this new book of poems, wrote his

mother to tell her that he had published enough poems for a

lifetime�was he thinking of Wyatt, who died in his forties? And I

see the same man who published that book, who posed for dozens of

publicity photographs in the last year of his life as if he would

need them for his revived career, his rediscovery, his reclamation,

his second wind after the midlife crisis of his 41st year

had passed.

Inspired impressions burn off like fog, and I need more to go on.

I return to the flyleaf. Whatever is on page 14 is "wonderful." And,

as I turn the pages, I get that feeling that the trail back is

getting cold. Something about the line weight of the penciled

annotations is not right, the loop of the terminating lowercase L.

Then there is that word, "wonderful," which Kees would only use in

irony.

The poem is Wyatt's rhyme royal chestnut from "Tottel's

Miscellany," known by its first line: "They flee from me, that

sometime do me seek." And Kees had already learned something from

the Elizabethans well before he bought his copy of

Silver Poets. Compare sensuous limbs of Wyatt's lover

When her loose gown from her shoulders did fall,

And she me caught in her arms long and small

to those of Kees's "daughter."

Death in certain war, the slim legs green.

Or, fed on hate, she relishes the sting

("For My Daughter")

Three hundred years span the composition of both lines. Masochism

and incest have replaced courtly love. Yet, if the alligator clips

of modern sensibilities could be hooked to the tender lines of Wyatt

remembering the sylph who no longer sleeps in his bed to Kees'

sardonic meditation on fatherhood ("These speculations sour in the

sun./ I have no daughter. I desire none."), the meter would register

like increments of pain and longing. I would need to go to another

Kees poem to see the same disappointment in the animal

performance of love:

Robinson afraid, drunk, sobbing Robinson

In bed with a Mrs. Morse, ...

("Aspects of Robinson")

Pages 22 and 23 are "magnificent." Page 32 is "equally

magnificent." More love poems. This isn't Kees. He would never

revere anyone so obviously. Kees's talking is more like the first

pages of his academic seriocomedy, the novel

Fall Quarter,

in which he imagined how he might have turned out had he earned that

Ph.D. in English literature at the University of Chicago, where the

Elizabethans were turned into a form of torture:

His professors had been unable, in spite of all their efforts, to

trip him up in his orals. He had fallen down on only one question;

he had been unable to furnish them with the date of Sir Thomas

Wyatt's death. It was regrettable, but he knew it now: 1542. He was

not likely to forget it again.

Then the sick feeling rises that I may have followed a college

boy marking out poems he might read on a date with Sylvia Plath.

(But this is the bad me talking, scaring myself more than it is some

animadversion aimed at someone. It is just as possible that I have

followed a person into this book who is a serious guy, perhaps even

a mensch for all I know.)

The same pencil that signed the other name to the flyleaf, the

son of Kees's friend Horace Schwartz, seems to have made the notes,

all of them. I get out some copies of Kees's handwritten letters. In

seconds, I can tell a difference that would be apparent even to the

collector of signed baseballs.

And I have not remembered to remember that Kees was a good

librarian once. He considered underlining passages hardly

sublimation, a way to appreciate a poem, a line. To him writing in a

book was dirty, like leaving a ring in the tub. This thing

he had he even worked into a short story he wrote working at the

Denver Public Library in 1940. In it a girl with "coarse hair "

chews her nails and writes in a copy of

Leaves of Grass:

"This is a dirty filthy book. I hate it." This was all Kees needed

to say what America really thought, too, of his kind of

books. In

Fall Quarter, it takes the form of

a little boy dressed in a department store Indian costume copiously

spitting in a rare volume. Kees himself even let on what he thought,

imagining the "value" of a collection that could have just as much

have been his:

When the coal

Gave out, we began

Burning the books, one by one;

. . . . . . . . . . .

They gave a lot of warmth.

Toward the end, in

February, flames

Consumed the Greek

Tragedians and Baudelaire,

Proust, Robert Burton

And the Po-Chu-i. Ice

Thickened on the sills.

More for the sake of the cat,

We said, than for ourselves,

Who huddled, shivering,

Against the stove

All winter long.

("The End of the Library")

|

|

|

Bookplate and signature on front flyleaf |

I turn around and backtrack out of

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century. Maybe "S. Schwartz" identified a few poems

that seemed to inform

Kees's work, underlined a few Keesian lines in the Wyatts,

but grew disappointed himself when he could not find some margin

note or some underscore that betrayed Kees's presence in the book.

Some lines underlined in pencil have the word "seek."

I start to see one of those Elizabethan anagrams. I have to stop

this. I have to let my maybes melt in my hands. One lone book from

Kees's broken library is not a small piece of Rosetta stone for

understanding him. It quickly turns from Lucy's jaw to the monkey's

shinbone. This "little find" is simply one of Kees's black peony

seeds. (They tick in the poem "The Testimony of James Apthorp.")

It is just a dot in the ellipsis that runs out from his short life,

which I tried to put end to end. And it won't be in the biography I

finished, that might lie for a time in bookstores that Kees can

never enter again browsing for that continuum he found in

Silver Poets of the 16th

Century, the one that keeps going on for whoever

holds his books, his poems:

"This age is not entirely bad."

It's bad enough, God knows, but you

Should know Elizabethans had

Sweeneys and Mrs. Porters too.

The past goes down and disappears,

The present stumbles home to bed,

The future stretches out in years

That no one knows, and you'll be dead.

("The Speakers")

|