|

How Robert Shaw Becomes Robert

Lowell in "For the Union Dead"

Like many great American poets, Robert Lowell was an

audacious reviser. Though he practiced misspelling

"Lowell" on his mother's casket while

writing "Sailing Home From Rapallo," the

poet's more usual method in his drafts, especially

during the

Life Studies years and just after,

typically displays a different type of bravado. His

poems from this period tend to be written widely (and

sometimes nearly wildly), then deeply cut: in the

end, surviving images and lines, rearranged to make

the finished poems, act like a series of carefully

spaced signal fires. To watch Lowell's ideas shift in

this manner then rise up reconfigured is to observe a

master craftsman at work.

It's especially notable that Lowell's drafts from

this era display the same tendency no matter how

apparently dissimilar the original material. When he

was transforming his autobiographical prose for

Life Studies, for example, Lowell's task was to sift

out the more narrative elements for the transition

into lyric poetry. When he wasn't beginning with

narrative source material, Lowell tended to construct

dense webs of association then winnow; this project

never seems less difficult than the prose to poetry

translation, as if the distance between draft and

finished poem was at this period in his career (as it

was not, for example, in the History and Notebook

years) something he actively sought. Surely he chose

such heavily associative subjects that he didn't

leave himself much choice. At the time this often

meant coralling one's ancestors; this was certainly

an early move in "For the Union Dead,"

commissioned for the June, 1960 Boston Arts Festival

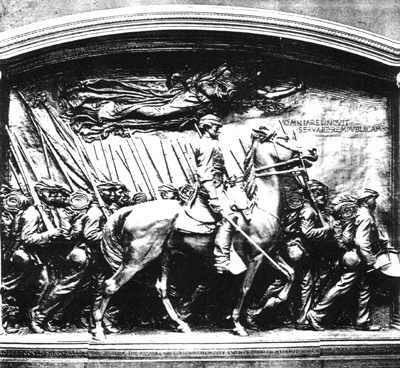

in Boston Garden, home to the famous Augustus

Saint-Gaudens bas-relief of Colonel Robert Shaw which

was already inscribed with a poem on the subject by

James Russell Lowell. Fortunately for Robert Lowell's

commissioned task and absolutely suited to his

method, these powerful dead heroes, artists, and, (in

the case of both Shaw and Lowell), literal ancestors

had been recontextualized by the twentieth century:

their Union had literally been shaken into new days

by such events as the explosion of the atomic bomb

and the Civil Rights movement and allowed to fall

into the hands of a successor who was both a

proponent of free verse and a conscientious objector.

That, as has been much-discussed, Robert Lowell felt

the need both to differentiate himself from these

ancestors and to distinguish his poem from earlier

renditions of the subject is most literally suggested

by a comment Lowell made about the poem's

construction: the poet claims he added "early

personal memories" to "For the Union

Dead" in order to avoid "the fixed, brazen

tone of the set-piece and official ode."

1

Inserting himself into the poem, that is, would allow

the poet to treat the Shaw material so as to avoid

the qualities of both the literal set-piece in

bronze, Saint-Gaudens' sculpture, and James Russell

Lowell's engraved, memorializing,

"official" verse.

To wrest this material from his predecessors,

Lowell needed both to recast it into his own

particular medium and to unseat the fixed and heroic

figure of the historical Colonel Shaw. In draft,

Lowell had tried to write about Shaw and the moment

of his death in an all-too narrative conclusion he

eventually made triumphant in "For the Union

Dead" by virtue of a double-dealing revision of

it into "...man's lovely/peculiar power to

choose life and die—" (Lowell, 71). But

what he seemed more attracted to in his earlier, more

narrative drafts were other Shaw stories,

particularly those about boyhood, as in this example:

so we are grateful you managed to supercede

those fond, early out of key anecdotes

how you ran away from school to your mother

or shaved your beard and mustache

and passed for a girl at the ball...

For the Robert Shaw of this version, heroism would

have had to come at the price of an all-too

interesting childhood: as Lowell says in draft,

"...As a boy you were too like us/ for us to

profitably wish to be in your shoes." The

revising poet knows that, like Shaw, he must

"supercede" such interesting

"anecdotes" to create a central figure who

is neither the buffoonish caricature of the more

narrative drafts nor the differently

"brazen" Shaw of the Saint-Gauden memorial

and the James Russell Lowell poem, yet who will both

reconfigure and dramatically recreate their shared

figure's complex triumph.

In the most literal terms, this means he will

substitute memories from his own childhood for the

"out of key anecdotes" of Shaw's. Lowell is

even more associative in making this move, however,

than the many fine critical readings of "For the

Union Dead" suggest, and his remarks on the

subject of "personal memory" are typically

both packed and disingenuous. By considering an early

association Lowell made and then cut in the drafts of

the poem which would become one of the great American

poems, we can see the labrynthine and truly

subversive way Robert Lowell worked himself into the

center of "For the Union Dead." We can also

begin to think of poetic revisions as he did, with

something of the Devil's own daring.

The addition of Lowell as a character in his poem

is the most discussed aspect of the poet's revisions:

however, a less spectacular but certainly crucial

decision was to bring Saint-Gaudens' sculpture itself

into the drafts—a move that invited the poet to

use art rather than history as an organizing

principle. In doing this he was able to free himself

from the temptation to arrange his poem in a

Shaw-like straightforward march or, as some versions

have it, "One Gallant Rush." This method

let Lowell work his subject out and back from several

perspectival vanishing points so that association by

way of images would create the poem's most prominent

pattern. By discussing Shaw through the medium of the

Saint-Gaudens memorial, Lowell is also able to extend

his gallery to include other suggestively similar

works of art: he claims that Saint-Gaudens' Robert

Shaw is like "Sintram," thus summoning into

the drafts both Baron La Motte-Fouque's 1814 romance,

Sintram and His Companions, and the

engraving it's based on, Albrecht Dürer's famous "Knight, Death and

the Devil." 2

|

|

"Knight, Death and

the Devil"

Albrecht Dürer, 1513 |

These are interesting choices, and obviously

compelling ones to Lowell, who used them in drafts of

several other poems, too, though each time, the

reference is eventually cut. The most unusual usage

is when he compares his grandfather's splintery gray

and watchful house to "Dürer's

Sintram" 3 —notably, the color and vigilance

he assigns to the house also show up in "For the

Union Dead." These qualities seem related to the

physical qualities of Dürer's print, its dense lines

and graduated grays. But it's easier than that to see

why Lowell thought of "Knight, Death and the Devil"

in connection with the Saint-Gaudens sculpture: at

the center of both is a classically posed military

figure who is nearly upstaged by the background.

That Lowell summons up other works of art in which

the background offers a challenge suggests that he is

prepared to embrace similar difficulties in revising

"For the Union Dead" away from the central

figure of Robert Shaw, and that his examples are of

complex artistic triumph also predicts his success.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, in fact, had remarked that

the decision to include background in his sculpture

was the first important revision of his idea: he had

originally wanted to make a free-standing statue.

When the sculptor, challenged by Shaw's parents to

include the men who died with their son, traded the

free-standing figure for a bas-relief with a horseman

at its center, the memorial was on the way to

becoming the triumphant public art that it remains

today. The addition of the soldiers of the 54th

regiment is considered to be Saint-Gaudens' most

daring and successful revision, far more important

than the sculptor's four-times re-worked angel of

death or the beautifully rounded horse, the original

of which was felled by pneumonia and died as a result

of the casting process. Saint-Gaudens in fact became

enthralled by the project, which fast outgrew his

commissioned time and money. So interested was he in

displaying a variety of African-American faces that

Saint-Gaudens modelled clay heads based on 40

different men on the street before choosing sixteen

individual profiles for the memorial, and in the

process he pushed the sculpture so far forward that

it could no longer be accurately called bas-relief. 4

|

|

Robert Shaw

Memorial

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

(Click image for enhanced view) |

Although we know less about its particular making,

the relation of background to foreground is equally

important in "Knight, Death and the Devil". Some

Dürer critics have objected to the heavily worked

background of the plate, claiming that the scenery is

of a different tradition than the foreground and

overcomplicated a fine study of a man on a horse

(Dürer himself called his print only "The

Rider"). But in a now-classic work on Dürer

reprinted four times between 1943 and 1950, Erwin

Panofsky argues that it is precisely the background

which endows the engraving with its essential

meaning: he describes blanking it out only to be left

with a figure who is "stiff and

over-elaborated." What Dürer got out of the

background, Panofsky argues, is the sense of what the

central figure—a Christian knight—must

overcome in the dark world through which he travels.

And the sense that he travels at all is provided by

the background through which he, his horse, and his

faithful dog point their profiles to indicate

"unconquerable progress" (Panofsky,

151-154).

What Saint-Gaudens achieves when he converts his

original idea for a statue into relief sculpture is a

similar sense of "progress": individually

striking as they are, the men of the 54th all face in

the same direction, ready to march forward to deaths

which are by implication waiting just over the edge

of the stone frame. This narrative is implied rather

than enacted, however, as is Dürer's Knight's

narrative. This sense of both implied and withheld

story gives both Dürer's engraving and

Saint-Gaudens' memorial much of their considerable

power: that the stories are withheld lets both works

press their emblematic and literal details forward

for our consideration. These summoned sources work

powerfully, too, for the poet who, in his final

choices for "For the Union Dead," also

suggests and withholds various narrative

possibilities by bringing forward what is essentially

background material. In all three works of art, the

achieved effect is of a central figure both set in

motion and reworked from behind so that their implied

progress is called into question. At the same time,

and as a result of this carefully crafted placement

in space, the worlds they inhabit seem simultaneously

both fully foregrounded and in possession of

extraordinary depth.

In both engraving and relief sculpture, of course,

this depth is literally made. The Renaissance

engraver pushes his burin into the copper plate, the

nineteenth-century relief sculptor pours molten metal

into a mold which itself has been shaped over another

material. Both processes involve production both

inward and outward and a literal reversal that seems

no less than magical: from incised and then inked

plate are lifted prints which reverse the plate's

image, from molds filled from the back with hot

metal, taut figures spring forward into view.

That the process of bringing forward what was

behind is risky is part of the technical challenge,

of course. Most literally, how much and how deeply

can a plate be incised? How far forward can relief

sculpture go before it either cracks or transgresses

the unseen plane before it? In terms of Lowell's

medium, how far can a lyric poem stretch its images

before they refuse to connect? In Saint-Gaudens'

sculpture, Dürer's engraving and Robert Lowell's

poem, such questions become part of the subject

matter and the source of each piece's lovely,

peculiar power. Shaw and his soldiers overcome the

difference in their conceptions and march off

together with the Angel of Death mirroring their

forward motion in air. Dürer's "Rider," on the other

hand, is issued a literal challenge from what's just

deeper in the background than himself: Death and the

Devil triangulate behind him, and Death's horse seems

ready to step ahead of the Knight's horse, halting

him in his tracks. In Robert Lowell's "For the

Union Dead," Robert Shaw's story is destabilized

by the poet's own background, which presses forward

into what the poem will eventually even refer to as

"space."

The technical challenge this presents is clearly

worth it to Lowell, as the alternative works of

public art he summons into his poem after excising

"Dürer's Sintram" demonstrate. That the

stone statues of the Union soldiers stand in contrast

to more vital, difficult art is obvious: while fully

rounded, the stone soldiers are downright dozy if not

quite dead, their narratives neither moving forward

nor acquiring depth. Without the pressure of

something behind them, that is, they become younger

and thinner, abstracted youths in sideburns; fixed in

their New England greens, they are set-pieces, close

cousins to the caricaturish pre-heroic Robert Shaw of

Lowell's early drafts.

They are, in other words, precisely what Robert

Lowell does not want his poem to be. Better to

threaten the poem's central figure and the poem's

cohesion than have it and its listeners fall into a

musing doze around the poet at a festival on Boston

Common. That the threat is aimed directly at what

stands in the poem's center is made clear by Lowell's

most daring rethinking of the Shaw material by way of

the Saint-Gaudens sculpture: the poet trades out

Shaw's means of "progress" by taking away a

crucial symbol of the classical military

hero—like the still more literal sculptor, he

kills a horse. Thus, what was an organizing piece of

subject matter in the sculpture becomes a vanishing

point in the poem; for both the forward motion and

"unquenchable progress" of the works of art

he summons into his drafts, Lowell then substitutes

his own symbol system, one which adroitly rounds the

material into his own.

There are many excellent, if somewhat bemused,

readings of the fact that Lowell offers Robert Shaw

riding on a twentieth-century "bubble."

Certainly, there have been very helpful discussions

of the way this particular image recurs in various

ways throughout the poem, linking the lost aquarium,

the cheeks of the soldiers, the exploding bomb, the

ballon-faced children and fish-finned cars. The

images of loss and death are so often reversed into

breath and life by means of this imagery in the

finished poem that Lowell's own comment preserved in

the drafts about "the blessed

break"—that at last black Americans seem to

be getting one—perhaps isn't as odd as it

appears. Yet while Lowell was adding what he calls

"personal memory" to the drafts in order to

achieve his lovely, peculiar poem, it seems important

that the bubble image, his own most original

contribution to the material, had been recently used

in the

Life Studies drafts. One more public

use of it, of course, had appeared in the

Schopenhauer quotation that opens "To Speak of

Woe that is in Marriage" which refers to the

"supersensible soap bubbles" by which the

future generation "presses into being"

(Lowell, 88). Unsurprisingly, the aquarium imagery to

which the bubbles are linked in "For the Union

Dead" has a more private connection as well: its

locus classicus is not only the South Boston Aquarium

of Lowell's childhood but the Payne Whitney clinic of

his adulthood, where, after the deaths of his

parents, he was asked to reconsider his childhood,

his "early personal memories," in an

attempt to mediate his manic depression.

That Lowell brings forward these associations from

his personal background helps him authoritatively

claim the movement of the poem which would become

"For the Union Dead" away from both

narrative sweep and out-of-key anecdote and

complicates even the background- to-foreground move.

Bubbles press both outward and up: they swell, bell

and 'blessedly break.' In his drafts of

autobiographical prose, Lowell links such imagery

directly to himself. While the adult Lowell character

in "For the Union Dead" can't touch the

bubbles and ballooned faces he yearns toward because

they are behind glass, the Lowell of the

autobiographical prose considered himself within the

glass: a resident of what he called a

"balanced" or sometimes

"unbalanced" aquarium where all conditions

are carefully calibrated for survival. 5 In the poems

taken from this material, Lowell claims something of

a bubble existence for himself. In the prose drafts,

Lowell had referred to the "yeasty rise" of

his madness, and when he revises a portion of his

prose into "Waking in the Blue," he uses

images of physical expansion: "I weigh two

hundred pounds/ this morning." This state he

contrasts with the "pinched, indigenous

faces" of his "shaky future": the

"thoroughbread mental cases/ twice my age and

half my weight."

That such associations from "personal

memory" occurred to Lowell when he was

constructing "For the Union Dead" is

suggested not just by the similar pattern of the

images but also by Lowell's excised reference to

Dürer's classical hero "Sintram."

Unsurprisingly, Lowell has reversed the order of

creation in his reference—Dürer didn't make art

out of an old tale of Sintram as he did out of the

Biblical story of St. Jerome or the miracle of St.

Eustace and the Stag. Rather, Sintram was a creation

of the early nineteenth century, and like the

Saint-Gaudens memorial and Robert Lowell's poem, was

the result of a "commission": a friend gave

Baron La Motte-Fouque a copy of "Knight, Death and the Devil" and asked him to create a tale from it,

a request the author includes in an explanatory

postscript at the end of the story he eventually

wrote. While

Sintram and His Companions is

perhaps unfamiliar to us, it was well-known and loved

by the Victorians:

Little Women's

Jo, for example, wished for the book in which it's

contained, Undine and Sintram, as a Christmas

present. From the first, this gothic tale is

organized less around dramatic forward movement than

around a cyclical series of encounters in which the

troubled Prince Sintram is harrassed by two

mysterious figures he eventually identifies as Death

and the Devil. Instead of moving with narrative

inexorability toward a final, fatal encounter, by the

time Sintram confronts his challengers for the last

time they've already met so often they no longer hold

a threat to the Prince: he has seen through all the

Devil's strategems, and the skeletal Death seems now

only a not-unkind fellow traveller. Indeed, the story

of Sintram is finally about how the hero manages not

to defeat Death and the Devil, but how he learns to

make them his "Companions." This is a

clever act of homage to Dürer's engraving, of

course, since it doesn't alter the Knight's pose, but

gradually changes the meaning of the relationship of

this central figure to his background. And, in a neat

psychological reversal, Sintram's Companions, who

initially seem to appear at random from a dense

Germanic forest, are eventually seen as as creatures

from within the hero: they are externalizations of

that which had terrorized Sintram since childhood:

his yearly bouts of Christmas madness. Robert Lowell,

himself subject to cyclical swells of manic

depression and cure, thus brings into the poem with

"Dürer's Sintram" not only the great

engraving but a narrative in which the hero confronts

his inner demons in the form of emblematic public

encounters and learns to think of them as part of his

journey.

By a most complex series of associations, then,

Robert Lowell manages to work himself into the center

of "For the Union Dead." He offers himself

as a both a challenge to and a twentieth century

descendent of Robert Shaw, not only as the bemused

child and adult of the poem, but, more audaciously,

in the image pattern which both unhooks the poem's

implied narratives and offers itself as the poem's

source of movement so neatly that Robert Shaw ends up

astride an image from the poet's personal lexicon.

Like Sintram, when he externalizes what's within, he

finds "Companions": in other words, he

invents a way for his poem's public and private

symbol systems to meet. And, brilliant reviser that

he is, Robert Lowell then cuts most of this out,

leaving us with a poem which is both light on the

page and utterly significant: anything but a

"set-piece." And yet Lowell is finally such

a great example as a reviser because, while he

invents broadly then cuts deeply, there is a sense in

his poems that nothing is ever quite lost. In the

hands of a master, the burin digs down but not too

far through, the figures push from the copper but

don't crack, the bubbles swell but, despite their

inherent tendencies, don't break, even blessedly. Ah,

we protest, but the hero's wonderful horse,

four-legged ballast of the sculpture, the engraving,

and the romance has been so thoroughly recast that

only a bulging flank remains. Perhaps. But we may be

simultaneously appeased and disconcerted to notice

that Colonel Robert Shaw has acquired, by the end of

Lowell's revisions, "a greyhound's gentle

tautness": Robert Lowell may have nearly

banished the horse within his defiant bubble, but

he's kept a little piece of "Dürer's

Sintram" by giving his central figure the

attributes of Dürer's engraved, heraldic dog.

Footnotes:

1. Lowell includes a one-page typed

discussion of the poem in the drafts of "For the

Union Dead" housed in the Houghton Library. All

subsequent references to drafts will be to the

documents in this collection.

2. Steven Gould Axelrod refers to

this connection in "Family Resemblance: Amy

Lowell's 'Towns in Color' and Robert Lowell's 'For

the Union Dead.'" Modern Philology 97/4

May 2000: 554-562.

3. This poem appears in the

"Uncollected Poems, 1951-1959" section of

the drafts.

4. Of the interesting discussions

of this piece, see particularly Dryfhout, 222-229,

and the National Gallery of Art Website, cited below.

5. Draft versions appear in

"At Payne Whitney" in the Houghton Library

collection. A version of the story may also be found

in

Collected Prose, 346-363.

|