|

Introduction

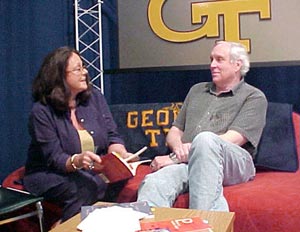

It's National Poetry Month, and I'm speaking with

Stephen Dobyns, who is about to conclude his semester

as the H. Bruce McEver Visiting Chair in Writing at

Georgia Tech.

Whether he's writing prose or poetry, Dobyns is a

story-teller par excellence, and whether he's writing

about courage or cowardice, the raucous or the

spiritual, the meek or the menacing, whether his

character is Orpheus or a Sad Sack getting a thrill

in a topless bar, Dobyns' poems are funny, full of

testosterone, and profoundly human. At first glance,

they appear casual in that they start simply enough,

but they pick up speed and hurtle the reader forward

just the way life does. He is witty, imaginative,

sometimes shocking, and always wildly original.

Dobyns is so forthcoming and generous with his

responses during the interview, what follows is a

course in poetry, and for that reason, TCR presents

it in two parts: Part I (below) discusses poetry in

general, but always as it stacks up against Dobyns'

own philosophy about what poetry is and is supposed

to do, and

Part II

(to be presented in

Issue 26) is an exploration into his

particular body of work—the progression of

Stephen Dobyns and the Stephen Dobyns poem book by

book.

—Ginger Murchison

Audio clips from the interview:

Rhythm borrowed from music

Rhythm borrowed from music

On Philip Larkin

On Philip Larkin

Following your idea

Following your idea

Defining one's self

Defining one's self

Invention of metaphor (Merwin's Asian figures)

Invention of metaphor (Merwin's Asian figures)

Sound as metaphor (Yeats' "Leda and the Swan")

Sound as metaphor (Yeats' "Leda and the Swan")

Stephen Dobyns

On Poetry — The Interview

TCR: The Georgia Tech Community and Atlanta,

both of whom have benefited from your work here, will

miss you, so I'm going to try to ask the

questions they'd ask, and they'd want to know more

about you, so describe Stephen Dobyns as a

twelve-year-old. What about him would have predicted

he'd be a writer?

Stephen Dobyns: I'm not sure

anything would have predicted that. I read a lot,

though at that time I probably read science fiction

and mysteries. I was a good writer then, although I

didn't have any sense of it. There were writing

exercises I had to do in grade school, and the

teacher would read them out loud—something I

took as a punishment rather than as

flattering—but she or he would be struck by

them, and then, I think, in the 7th grade—the

6th grade was in East Lansing, Michigan, and the 7th

grade was in Arlington, Virginia—I started

reading stuff that was, I suppose, more adult. I

remember looking through the school library for

another science fiction book, and I found

Steinbeck's

The Moon is Down, which

struck me as a science fiction title, and it led me

to reading Steinbeck, and from there, Hemingway.

TCR: Do you remember what you were reading

the first time you thought I can do that?

Stephen Dobyns: I don't think I

ever thought that. What I felt was I wanted

to do that. When I was 15 or 16, the poetry I knew

was mostly what was taught in high school and junior

high school. It tended to be nineteenth-century

poetry and, whatever my feelings were, I remember

liking Browning's "To His Last Duchess,"

but I had no sense of its being something that I

could do or wanted to do. The language was too

different from my own.

About that time, though, they started

reading poetry to jazz, and I was very struck by

that. There was one album of William Carlos Williams

and Walt Whitman; there were other albums of

Ferlinghetti and Rexroth reading, and then an album

of Langston Hughes reading, and I started reading

poetry and thinking I wanted to write it.

TCR: So music was the hook. I know you're

very deliberate about the rhythm of the line. I've

seen you tap out the lines with your foot or finger

while you read.

Stephen Dobyns: That's true. My

father had been a musician and had gone to Julliard

to study piano, but he left there to go to graduate

school at Columbia in music. He didn't like teaching

high school music and went into other work, but there

was music in the house a lot; he was musical, my

mother was musical, my brother plays various

instruments, my son plays various instruments. Many

times I've gotten rhythms from music, not necessarily

transposing the rhythm of a song into the poem, but I

keep taking it into consideration. I remember a poem

that I wrote in graduate school in Iowa—probably

about 1965 or so. The first line was:

You pick up your purse, I speak, you

smile,

and that ba bop ba ba bop ba bop ba bop

struck me as a straightforward rock and roll rhythm.

TCR: I guess that's what you meant when you

said you listen to music to steal.

Stephen Dobyns: Exactly. Mostly

it's not a clear-cut transition from one to the

other, but I listen and think how I could do

something like that.

TCR: Taking into account the magnitude of

your work and the excellence of it, regardless of

what genre you're in, suggests that you are driven to

write. Explain what drives you.

Stephen Dobyns: I suppose

there's a need to translate my experience of the

world into language. Things are most palpable to me

in language. Obviously, we live within time, and time

is constantly going by, and a poem or anything you

write, really, attempts to freeze a moment of time.

I've always felt a need to do that as

well... something I saw, something I experienced. The

poem is not necessarily directly about that

experience, but it is a metaphor for it, and, too,

there's the pleasure of putting the words together,

of trying to articulate things in a particular

manner, whether it be in the complexity of image or

the complexity of sound. That's always a task: to see

if you can do that.

TCR: After all these poems and all these

books, it's still a task?

Stephen Dobyns: Sure. I haven't

learned everything. I haven't learned half of

everything.

TCR: Maybe that's why I don't see you

involved in a lot of self-promotion. It seems as if

you write, going where the writing takes you, without

getting caught up in self-importance. I respect that.

Stephen Dobyns: I don't believe

in self-promotion much. I think you choose either the

work or the life. There certainly are poets who

choose the life, who are into self-promotion, and

that's what they are.

You

can't allow yourself to be hesitant in a poem. You have to think

what the poem needs, and you have to be frank with it.

TCR: Who or what is Stephen Dobyns? Can you

define him?

Stephen Dobyns: I think something can only be

defined when it's settled. I see the work as

changing, see the books as different from one

another, so it would be hard for me to make a

definition. Also, I'm not sure I want that

consciousness of myself. One of the things I try to

avoid is self-parody, and if I were to sit down and

try to define myself, it would seem an immediate

limitation. Language is always a diminishment of what

it's attempting to describe, and thinking of the

critical terms we know, all those which are

critic-based are, for the most part, a diminishment

of an idea.

Charlie Simic is a poet I admire and whose work is

very consistent. In the almost forty years of poetry

that we have from him, while there are certainly

changes within Simic, they are very slight changes,

and you can always recognize a Simic poem, so I

suppose it might be easier for someone like Simic to

define what he is doing. I am working within the

genre of poetry, and that permits me a lot of room,

whether it be the prose poem or a very traditional

poem or different kinds of free verse poems.

TCR: That's

pretty evident in the range of the work you've

published. I will get more into the work, but for now

I'm going to make a personal observation, and I look

forward to your correcting me if I'm wrong, but

socially you are very quiet and seemingly much more

inclined to listen than to jump into the argument,

yet your poems are full of opinion, they are

visceral, raucous, and speak in a voice that is

anything but reticent, and one that seems to come

quite naturally, so what happens when you pick up the

pen? Whose voice are we hearing in the poems?

Stephen Dobyns: It's my voice. I can be

argumentative when I need to be, but I once heard a

guy at a meeting say that when he felt inclined to

talk, he asked himself: Why am I saying this? Do

I need to say it? Do I need to say it now? That

made me realize that a lot of human speech is

jockeying for position, and so before I speak, I want

to know if I'm trying to reflect some credit on

myself. That sometimes makes me more reticent than I

might otherwise be. I don't want to use my speech to

set me off or see that other people are impressed by

me. That's just smoke and mirrors.

TCR: That

shows a huge respect for the language and for other

people, and it speaks again to your unwillingness to

self-promotion. I'm awed at that kind of generosity.

I'm also in awe that you can write in so many

genres at once and move, apparently easily, back and

forth between them. Even Faulkner, you know,

described himself as a failed poet. He said:

Maybe every novelist

wants to write poetry first, finds he can't and then

tries the short story, which is the most demanding

form after poetry. And failing at that, only then

does he take up novel writing.

If I remember right, that's not the way you did it. I

think you wrote poetry first, then novels, then short

stories, but comment, if you will, on how you keep

all of that on your desk at the same time and move so

easily between them.

Stephen Dobyns: They're all different ways of

using my mind. The first things I wrote—I was in

high school—were little short story things,

little descriptive paragraph things. I also did some

journalism in high school, and then in college I

wrote some poems and some fiction and took a

playwriting class and tried to write some plays.

Obviously, I wrote papers in college and afterward

began working as a general assignment reporter for

the Detroit News, and since about 1995, I've

been writing feature stories for the San Diego

Reader.

They're all just different ways of trying to describe

experience. I guess I would agree with Faulkner. A

lot of novelists whom we think of as major novelists

also wrote poems: Joyce and Hemingway have poems as

well—pretty bad poems.

I hadn't taken short stories seriously for a long

time because I didn't think I could do them, but I

read stories by Chekhov, the writer I probably admire

more than any other, and I read other stories,

certainly, but once I started writing short

stories—the ones that finally came out in the

book

Eating Naked—I saw that

they came out of me much the same way poems do. I

mean, I write poems to find out why I write them,

whereas, with the novel, I have certain ideas and put

those down in notes and continue to build those notes

until I have a sense of the whole novel, and then I

outline those notes and have character sketches and

all kinds of stuff. There's still a lot of discovery

in the novel, but I have a sense before I begin of

the curve of that novel—the beginning, middle,

and end.

Language is

always a diminishment of what it's attempting to describe, and

thinking of the critical terms we know, all those which are

critic-based are, for the most part,

a diminishment of an idea.

TCR:

Speaking of discovery, you said once that you've

written the same poem over and over, not so that the

reader would ever recognize it, but that you keep

looking at the same thing over and over. Would you

speak to that? What are you after?

Stephen Dobyns: One of the writers I admire

most is the poet Philip Larkin, and I think often of

his work. He is absolutely tenacious in following a

subject; he's like someone who turns over rocks to

study the bugs that exist underneath, and the human

experience is like that, which is obviously a

pessimistic view, but it's one, nevertheless, that

reflects in Larkin. It goes back to the question of

what it is to be a human being, to look closely

enough to come to some kind of answer. Our mood is

changing all the time, and our psychology is slightly

changing or modifying, so I might look at something

and come up with one thing and look at the same thing

a week later and come up with something else. The

answers are like things that exist around it. You

define the space of something by occupying the space

around it like a mold. You keep coming at it from

different directions.

I'm trying to deal with the world, to understand it

in some way, to pass to some other kind of level

below its surface. The question—it's been

said—that exists in every work of art, poetry or

fiction and, I suppose, maybe even in music and

painting, is the question How does one live?

A writer addresses that question again and again,

sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly.

TCR: So, like

Larkin, even after you've written the poem one

way, you keep walking around the same subject,

exploring what it means from some other place,

another place in time and so another place in your

mind.

Stephen Dobyns: Exactly. This is something I

read in Yeats's autobiography when I was 22. Yeats

wrote two autobiographies, really. There was one that

was not published for many, many years called

The

First Draft, but in the other one, the one

actually called

Autobiography, he

says that we tend to write about the same things all

our lives, that the subject matter we have as young

adults is the subject matter we have as old adults,

and I thought—at 22—that that was an

absolutely horrible idea, yet as time goes by, I feel

it certainly is true. We have concerns as human

beings, primary concerns that exist all our lives.

Since we change during our lives and our insight also

changes, we approach those concerns differently over

a period of, say, forty years, but they're the same

concerns.

TCR: I guess

it's that looking back and looking back again that

elicits the truth of things, and you do get

to the truth, but not just the truth of the idea. You

get to the truth of the reader, and that

lends an incredibly human element to your work. I'd

suspect that even people who don't particularly like

your work respect your willingness to face up to the

hard fact of your (and our) humanness, but I can't

help wondering if that kind of honesty isn't possible

only in a perceived world. Do you think we can stand

a view of ourselves that's that honest?

Stephen Dobyns: I think we can. It's hard

because we are obviously always in motion, and we

don't necessarily stop and focus on what we are

doing. Psychoanalysis, or seeing a therapist can lead

us to a deeper sense of ourselves, but one doesn't

need that. One can find that through an experience or

one can find it through reading. Look at a novel like

Tolstoy's

Anna Karenina. The depths

of character that come out of that book are very

enlightening, and they're enlightening because we

realize that people around us also have that

complexity of character as do we ourselves, that we

have a conscious mind that is looking around us and

taking in the stuff around us, and then we have an

unconscious mind that's doing the same thing but

which is much harder to have any sense of. I mean we

see it in the effects of its actions rather than in

its causes. There are plenty of people who don't like

my work. I was dismissed just the other day as

"one of those accessible poets."

|