|

JM: Bob Moses—what was he like?

WH:

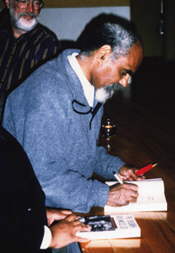

He has literally what I would call prophetic aura. He has this charisma, this

magnetism, this sense of spiritual depth, this seriousness and at the same time

a kind of tenderness and care that goes with your image of a certain type of

guru figure—a spiritual leader. And his face conveys that as well. He’s got

these very dark eyebrows and very deep eyes, and you have the feeling that there’s

something absolutely penetrating about his gaze both into you and into the

larger picture of things. This is a guy with levels, with depths within depths.

That’s very intriguing, and it’s very rare. Most of the heroes of the Civil

Rights Movement were men of action and bravado and were sort of doing, "I’m

tired of taking this shit, and now I’m going to fight back." Certainly,

Moses had those feelings too, but you had the feeling that this is a guy who is

looking way down the road and planning his moves way in advance. WH:

He has literally what I would call prophetic aura. He has this charisma, this

magnetism, this sense of spiritual depth, this seriousness and at the same time

a kind of tenderness and care that goes with your image of a certain type of

guru figure—a spiritual leader. And his face conveys that as well. He’s got

these very dark eyebrows and very deep eyes, and you have the feeling that there’s

something absolutely penetrating about his gaze both into you and into the

larger picture of things. This is a guy with levels, with depths within depths.

That’s very intriguing, and it’s very rare. Most of the heroes of the Civil

Rights Movement were men of action and bravado and were sort of doing, "I’m

tired of taking this shit, and now I’m going to fight back." Certainly,

Moses had those feelings too, but you had the feeling that this is a guy who is

looking way down the road and planning his moves way in advance.

For me, that was what was so interesting, that he had this sort of depth of

soul that you rarely find. The rap on Americans is that they’re superficial

and innocent and na�ve and sort of frivolous, and often that’s all too true.

Yet here’s a guy who’s the counterpoint of that. This guy is solid in a way

that’s very, very impressive. And his style of leadership was in some ways the

polar opposite of Martin Luther King’s. King was one of the great orators of

our time, and the Civil Rights Movement knew that and decided to make him the

media hero. And so wherever King went, the media went, and crowds gathered in

big numbers. King would go to the church and give his big sermon, and everyone

would shout and sing, and then King would say, "Let’s march here,"

or "Let’s do that," and everyone would do it. But then the next day,

King gets on his plane, and the media goes with him, and the community is left

feeling drained and directionless. Moses’ idea was to unobtrusively come into

town and organize the leadership of that town so that they defined their own

goals and their own leaders and became a self-motivated and self-perpetuating

system. Much of the history of the Civil Rights Movement is not of following

King’s charismatic path but of looking at all these local people who did

courageous things in their local communities. The best history book on

Mississippi in this period is by John Dittmer and is called Local

People [University of Illinois Press].

That’s really the story—it’s the story of local people. And Moses was

at the core of this notion, that local people will be the story and that we can

make them make a difference. The catch is this contradiction between the fact

that here’s this guy who holds this prophetic aura trying to be unobtrusive.

People picked up on the fact that wow, this is not your normal guy; this is

someone who has spiritual vision. Moses would encourage people to have town

meetings and discuss their problems and stay in the back and be quiet, but

before the evening’s out they might say, "Bob, what do you think?"

And he might just whisper a few words, but everyone would say, "Yeah!"

He ended up being more of a leader than he wanted to be, in effect. Toward the

end—I allude to this in the afterward of my novel—after the Democratic

Convention, Moses changed his name because he felt that the power of his

spiritual charisma plus the name of "Moses" among these Southern

blacks with such strong religious faith—I mean that was a knockout. He also

said to another guy in the Civil Rights Movement, "No one will call me a

son-of-a-bitch. Everyone respects me so much they won’t talk back to me. And,

you know, I don’t feel like a normal guy among normal guys under that

circumstance." So he actually changed his name to Robert Paris, which was

his mother’s maiden name.

Anyway, the reason I called the novel The

Children Bob Moses Led was to dramatize this issue of leadership,

sort of the "King style" versus the "Moses style," and what

does it mean to be a leader, what does it mean to be a follower, and what the

consequences are of a certain kind of leadership and a certain kind of "followership,"

if that’s the word. In a sense, Moses is the leader and Morton is the

follower; Moses is the hero and Tom is the neophyte, and you play back their two

versions of what the Civil Rights Movement meant through their two voices and

their two sensibilities. And then of course all the other characters add further

counterpoints and further variations.

JM: Had you thought about having an omniscient

narrator, as opposed to having Moses and Tom Morton narrate sections of the

novel?

WH: A major decision every novelist has to make is what your point of

view is going to be. I guess the major motivation was that I very much wanted to

create a sense of immediacy, a kind of "you are there" feeling. The

Civil Rights Movement is getting lost to our collective memory, the history

books are too concerned with generalities to recreate it in a nitty-gritty

experiential sense, and the TV is all sort of hackneyed and clich�d, so the

trick is: Can you create a novel that brings it all back? The general sense was

that first person, if you do it well, creates a sense of immediacy and a

presentness.

JM: You attended the march on Washington—is

that where the seed was planted?

WH: I suppose so. I sort of wandered into the march on Washington

without design. I had been teaching tennis up at a tennis camp in the

Adirondacks and had come down to visit a friend of mine in Washington, and he

had been planning to go and was more into Civil Rights than I was. But the real

appeal for us was Bob Dylan, Peter Paul and Mary, and Joan Baez—all our

favorite folk singers would be there. We really went for that reason—a free

concert, in effect—but, nonetheless, here we were taking part in one of those

great moments in history. So when we got back to school—this was in very late

in August—we had the status on campus as the "Civil Rights Gods,"

you know. [Laughs] I guess I got an identity as someone active in Civil

Rights for a free afternoon in Washington listening to rock music. In a way, you

feel you have fraudulent credentials, although I was concerned with Civil Rights

and took part in some minor stuff. I worked on the Carl Stokes campaign in

Cleveland, who was the first black mayor elected in 1973. I canvassed in

Kentucky for various candidates. I was actually more politically active than I

am now, in the sense of hitting the streets and knocking on doors and trying to

get some things done.

JM: We’d spoken earlier about people who write

for a little group of true believers, who see themselves as having a special

notion of what the novel should be. What about poetry? Do you think a lot of

poetry does that?

WH: There’s a real tendency to do that. With poetry it’s trickier.

You ask the poet to go off in strange little places. The poet does not have that

same obligation to write the history in the real world, the dialog and all the

rest. But certainly you can overdo it. There’s that wonderful poem by Edward

Field—do you know him?—he writes sort of prosy poems, really witty, where he

says, "Save me, O God, from poet’s head, that dread disease." [Laughs]

"Poet’s head"—oh, I know what that is! It’s like, "People,

I am a poet. Anything I say is poetry. Watch me roll." It’s a kind of

mental illness. I mean, it can be a charming mental illness, or the guy can be

the most obnoxious person on the planet.

JM: Over time the pleasures we derive from

writing change. How have they changed for you?

WH: One of the tricks is that as you get older you do become more

critical of yourself. We were talking about how I think I screwed myself up as a

poet by setting my standards too high at certain points, so I suddenly stopped

writing. I think all writers have to be schizophrenic in a certain sense—your

first inspirations have to be uncensored. You have to sort of let it pour out,

tap into the Dionysian or whatever and get it out on the page and get expressed.

Then once you have that initial enthusiasm or inspiration, then this prim little

school marm has to come in with a red pencil and chop it all up. And it’s very

hard for writers to combine those two personalities. I mean, you have to be

Dionysian in the morning and Apollonian in the afternoon. You have to be this

crazy visionary for a few hours and then this prim little proofreader, and to

have the ability to combine those two things is very tricky. Probably the reason

most poets write well when they are young, is that the Dionysian comes out more

easily when you’re young. You can always come back when you’re older and

revise the stuff and sharpen it, but it’s probably harder to tap into that

stuff if you have too many censors already out there saying, "That won’t

work. That won’t fly. That’s trite." If you’re too self-conscious

about that it can dampen your creativity. I think that’s part of the problem—keeping

those two selves in balance, the inspirational self and the craftsman who comes

in and wants it all perfect and won’t forgive you for a misplaced comma.

JM: The muse won’t leave you with a particular

feeling of a poem that long anyway. Even with some of our best works it just

leaves you, and you can’t really go back later—

WH: And pick it up and that whole biz. We were talking about

"poet’s head." People with poet’s head are often people who have

the first half of being a poet but not the second half. They love letting it all

out, but they don’t love sorting it all out and putting it into shape—

JM: Being the

craftsperson—

WH: Right, and making it actually make aesthetic sense. But you can

get away with that on your average Poetry Night.

JM: I guess that all gets sorted out to some

extent in workshops, although I don’t want to put myself as a purist.... But I’ve

never actually approached poetry from any kind of academic sense, so I have

never actually been a part of the whole workshop phenomenon. My revision just

simply comes from wanting to be as good as what I read, you know, or in that

ballpark somewhere.

WH: Sure. And I think that makes good sense. I sometimes bemoan the

fact, though it’s probably also good luck, that I never had creative-writing

teachers because I never took creative-writing classes. I’m not a disciple of

this writer or that writer who kept fixing my work until it was like his work.

You pay a price both ways, because you can be very na�ve about what you’re

still doing wrong. Sometimes a professional can say, "No, get rid of

that." But at the same time, so many people come out of this workshop

system—it’s a strange phenomenon—we must have 100,000 people studying

creative writing, and we’re not coming up with 100,000 great creative writers

every year. Somehow this isn’t quite working.

JM: Somewhere along the line you’re turning

out decent craftspeople without the muse, or you’re turning out a lot of

people with the muse who can’t get the craft down.

WH: Right, or whatever. There’s that famous quote from Flannery O’Connor

when she was asked if creative-writing classes stifled writers, and she said,

"I don’t think they stifle enough of them." [Laughs] There is

probably a need for some people to stop and to drop by the wayside. I think one

of the big problems is that there’s poet’s head and there’s novel’s

head, and you get so infatuated with your own work that you lose the ability to

actually judge it and to appreciate people who are doing it better. There’s a

great quote by Milan Kundera where he says, "We’re being drowned out by

the noise of human certainties, and everyone eventually will see themselves as

an artist," which means that everyone babbles away without listening to

anyone else. And that’s the death of civilization.

JM: You know, you take a magazine like Poetry,

which receives 80,000 submissions a year. Obviously Poetry doesn’t have

80,000 subscribers—that makes you worry.

WH: That’s one of the ironies—there are more people circulating

manuscripts than are reading anything of worth. And of course if you’re not

reading anything of worth, how can you possibly improve your own work. You

should be spending more time reading and less time writing, and trying to figure

out what’s good and then trying to figure out something good that you can do,

too.

JM: When I speak with my contemporaries, whom

are also writers, I find a surprising ignorance of the living poets. I’ll just

pull a name out of a hat—R. T. Smith, who is from the area, or Greg Djanikian.

You see that ignorance, and maybe that’s a strong word, but that seems to be

the problem is that they’re not aware of who the living writers are.

WH: Right. They haven’t even checked out the competition. I mean, in

basketball you can get all these people who can give you an exact discussion of

the 10 best power forwards in the league and why this one’s better than that

one, but in literature it’s difficult to find anyone who can make fine-tuned

discriminations about this writer versus that writer because we’ve lost that

ability to really read well and set high standards and figure out how you sort

it out. It’s sort of like we’re all playing a game, and there are no umpires

anymore, no score-keepers. In a way, we want it that way because then everyone

can have their own little ego game, but on the other hand you lose that sense of

your nation. We need more writers who are, as Joyce said, "Creating the

uncreated consciousness of the race," you know, expanding our sensibility

and our awareness of what the world is about. And we have to be right in our

judgments of that because if you’re modeling yourself after writers who aren’t

very bright and aren’t very insightful, then you’re not that bright, you’re

not very insightful. We already have this problem with mass culture, which is

persistently dumbing us down, and we have the in-turn problem that if we misread

our elite culture, if we worship the wrong gods and follow the wrong leaders, we

run the risk on the other end, of outsmarting ourselves on the negative end,

admiring what we shouldn’t admire and adopting styles we shouldn’t adopt. I

think all these things matter, but it’s very difficult to do this kind of

judgment.

JM: Thom Gunn had a poem called "Jamesian,"

which was about two lines long, on the New York City Transit System.

WH: Yeah, New York City had a program for poetry in the busses and so

forth. [Poetry in Motion —Ed.] That was really fun, but you wonder how

much difference it made.

JM: Gunn related a story about his poem "Jamesian,"

which appeared in one of those adverts. The poem goes like this: "Their

relationship consisted/In discussing if it existed." And apparently,

someone had written a piece of literary criticism on it, which read, "And I

didn’t get no [expletive deleted] either." [Both laugh]

We’ve talked about the popularity of poetry, but what

about the popularity and impact of literary fiction. What do you see happening

to literary fiction in the future?

WH: What seems to be happening, in general, is that mass-culture

fiction is swamping serious fiction, and fewer people seem willing to make an

effort to point out that what passes for fiction these days is usually not the

real thing. If one were to divide the novels published today into categories and

percentages, it would quickly become apparent that the vast majority of fiction

published is formulaic escapist fantasy. This, in turn, breaks down into male

and female genres, with the men reading thrillers and sci-fi and women reading

soap operas and romances. Now since the cultural arbiter nowadays is the media

journalist, you will never see anyone, say, on television, point out the fact

that the writer being interviewed that day writes, essentially, crap. Instead,

Danielle Steel, John Grisham, Stephen King, to name only the most famous, get

treated as if they were real writers of genius, instead of hacks who happen to

have a fantasy life on a par with the average American page-turner.

On the other hand, there is a tendency in the small niche reserved for

serious fiction to settle for brand names with no serious attempt at literary

evaluation. And so a lot of pretty bad books by pretty well-known authors again

get treated as though they were masterpieces, while some pretty good books by

some basically unknown authors get totally ignored. There hasn’t been a

serious attempt to evaluate contemporary American fiction in thirty years! I

think the last book to even come close was Tony Tanner’s City

of Words, published in the 1970s, and his book is guilty of

leaving out some major figures—Thomas Berger, for example—and spending too

much space on lesser figures.

In sum, we have a mass culture that continues to dumb us down and a

dysfunctional elite culture that often outsmarts itself and puts all its money

on the wrong horses. I don’t know that there are a lot of great writers among

us these days. I rather doubt it. But I do know there are a lot of very talented

people making a very serious effort to write good fiction and that this culture

has lost interest in keeping track of who our good writers are and what books

are truly worth reading. Obviously, I think all this matters enormously. I would

like to think that someone looking back on our time period from the next century

would not have to conclude that we were all fools and scoundrels infatuated with

pseudo-writers and pseudo-books.

__

Interview with William Heath

TCR 1999 July Feature

< back to

main page

|