| FEATURE |

|

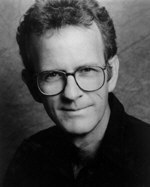

Mark Jarman |

|

J.M. Spalding interviews the poet. |

John Kinsella |

|

The River - Initial chapter of John Kinsella's

autobiography series at TCR. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mark

Jarman is the author of five collections of poetry. He has also written a

book-length, narrative poem, Iris.

With David Mason, he has edited Rebel

Angels: 25 Poets of the New Formalism, and with Robert McDowell, he has

written The Reaper Essays. Jarman's awards include

fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim

Memorial Foundation. His book The

Black Riviera won the 1991 Poets' Prize. Questions

for Ecclesiastes was recently awared the Lenore Marshall Prize. Mark

Jarman is the author of five collections of poetry. He has also written a

book-length, narrative poem, Iris.

With David Mason, he has edited Rebel

Angels: 25 Poets of the New Formalism, and with Robert McDowell, he has

written The Reaper Essays. Jarman's awards include

fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim

Memorial Foundation. His book The

Black Riviera won the 1991 Poets' Prize. Questions

for Ecclesiastes was recently awared the Lenore Marshall Prize. His

book of criticism, The Secret of Poetry, is forthcoming from Story Line

Press, as is his next collection of poetry, Unholy Sonnets—of which

poems appear in The Cortland Review Issue Four.

He teaches at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. |

|

| Interview

with Mark Jarman |

|

J.M. Spalding: Mark, first let me say that it is a pleasure to do this interview

with you. Today I’ll start off with an easy one: What is the first thing you notice

about a poem?

Mark Jarman: The first thing I notice about a poem, if I am reading

it, is its shape on the page. After that, I notice all sorts of things. I wish I could

claim that, like W. H. Auden, I looked first at what the poem was doing technically. But

that's not altogether true. I read the poem and expect it to move me. For that to happen I

have to notice everything, of course, consciously and unconsciously. In one poem it will

be an apt and surprising metaphor, in another it will be a particular way with rhythm. My

experience of listening to, rather than reading poetry, is distinct in some ways. If I am

listening to a poem for the first time, without the text before me, especially if the

author is reading it, then I notice a quality of voice, rhythm, and surprise. And, as when

I read a poem on the page, I expect to be moved by what I hear.

What are some poems that move you?

Many poems move me, so many that it would be hard to make even a short list. Aptness

and perfection in poems move me as I suppose they move anyone who cares about such things.

But I also greatly admire those poems which are not perfect, but nearly perfect, as they

render human imperfection or, more precisely, show themselves to be products of human

imperfection. I'm thinking of Emily's Dickinson's "After great pain, a formal feeling

comes—" (poem #341):

After great pain, a formal feeling comes—

The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs—

The stiff Heart questions was it He, that bore,

And Yesterday, or Centuries before?

The Feet, mechanical, go round—

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought—

A Wooden way

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone—

This is the Hour of Lead—

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow—

First—Chill—then Stupor—then the letting go-

This poem moves me because it appears that the poet has not decided exactly how to

represent this kind of grief. Though the images all have numbness in common, they embody

variously stillness and movement, rather like the indecisive motions of characters in a

Beckett play or a Bergman movie. The uncertainty of the form also moves me, because of the

exactness in which each part is executed. It begins uncharacteristically for Dickinson

with two iambic pentameter couplets, though the first half-rhyme is typical of her

rhyming. The middle stanza seems to lose its way as she heads back to her preferred form,

common measure. The stanza is five lines instead of four, lines three and four should form

one line of iambic tetrameter, not two of dimeter, and the fifth line is extra, and it

includes an imagistic surprise, with its crystalline paralysis. Amazing. The final stanza

is just as much of a departure, beginning with a trimeter couplet, in which

"Lead" and "outlived" rhyme only by the sheerest indulgence. The final

two lines form one of the most powerful iambic pentameter couplets in the language. The

poem is perfect in each part, but as a whole it is a mechanism of incongruities. I think

of the voice at the end of Beckett's The Unnameable, saying, "I can't go on.

I'll go on."

Poetry that makes me believe in a place or a landscape moves me. One of my favorite

poems is W. H. Auden's "In Praise of Limestone." The end of the poem is

incredibly moving, because he admits to knowing nothing about what he calls "a

faultless love" or "the life to come," but when he tries to imagine them,

he hears "the murmur of underground streams" and sees "a limestone

landscape." I suppose it is when a poet admits to being human that I am moved, but

especially when he or she tries to imagine something more than human.

In "Education by Poetry," Robert Frost says that poetry is the philosophical

attempt to say matter in terms of spirit and spirit in terms of matter, to make what he

calls "the final unity." But he adds that it is an attempt that fails, because

ultimately all metaphors break down. I am moved by poems that recognize the limitation of

their expression, even as they try to transcend that limitation. The end of Brenda

Hillman's "The First Thought" from her book Bright Existence is a

wonderful example. Describing the birth of her child, she turns suddenly to the reader,

and asks, "don't you love the word raiment? / Dawn comes in white raiment. /

Something like that." The humility and beauty of an inadequate

phrase—"Something like that"—moves me much more than a simile that

might make a greater claim. Nevertheless, I think there is no other way to say what

Hillman says here. To me it is as apt and perfect as one of the Beatitudes, for example,

"Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God." I find the Beatitudes

and all the poetry of Jesus intensely moving, too.

You have made your living as a teacher. Could you talk about some

of the rewarding experiences you have had teaching?

Perhaps the most rewarding experience I have had as a teacher was learning that I liked

to teach. That was about the time I turned 40. I had been teaching since college,

actually, when as a senior I taught an undergraduate-directed poetry writing class (a

special feature of my college at the University of California, Santa Cruz). Then, I taught

as a teaching/writing fellow in graduate school at the University of Iowa Writers'

Workshop. One of my students there was the poet Nancy Eimers, an undergraduate at the

time. Teaching professionally was something that happened because I needed a job after

graduate school, applied for a few, and was lucky to be hired by a branch of Indiana State

University in Evansville (now the University of Southern Indiana). The course load was

killing, three freshman composition courses and one creative writing course per semester;

I was totally unprepared for that kind of work. Nevertheless, I had some talented

students, one of whom, Barbara Hass, has gone on to a career as a fiction writer. While it

was gratifying to have talented students like Nancy Eimers and Barbara Hass, during my

first years as a teacher, teaching still seemed merely like a way to make a living while I

wrote. And it continued to be that way through many positions: a visiting lecturer

position at the University of California, Irvine, where two members of the graduate poetry

workshop that I led were Garrett Hongo and Yusef Komunyakaa, three years at Murray State

University in Kentucky, and my first nine years at Vanderbilt University, where I now

teach.

At Vanderbilt I have also been fortunate to have some talented students, especially the

poets Greg Williamson and Terri Witek, but as I say, it was not until six years ago that I

realized how much I enjoyed teaching and how rewarding the experience of teaching was to

me. Perhaps turning 40 endowed me with a paternal air of authority, making it easier for

me and the class to believe what I was saying. I have been privileged at Vanderbilt to

teach poetry writing classes and classes in literature, including upper division classes

in contemporary poetry and a graduate seminar in the poetry of Robert Frost. Teaching has

been rewarding to me because I am basically an incorrigible student; I want to know the

answer and I want to be the one to give the answer, which is one of the reasons why I

don't think I'm as effective as many of my colleagues who are dedicated teachers. Still,

it has become a great pleasure to me to see young people learn to articulate their

thoughts about poetry, as well as to begin to learn the craft of writing it.

Mark, you were born in Mount Sterling, Kentucky. Could you talk

about that environment and how it influenced you as a young writer?

My parents left Kentucky when I was two. My father had gone there to attend seminary at

the College of the Bible in Lexington (now Lexington Theological Seminary). They were

Californians, and when my dad's course work was done, they returned to California. While

in seminary my father served a little church in Sharpsburg, a town of 400 people; the

hospital where I was born in the larger town of Mount Sterling

later burned down. It would seem, then, that Mount Sterling and environs had little or

no effect upon me. But my father was and remains a good amateur photographer and took

many, many pictures of his parishioners and recorded their lives and the life of the

church he served. When my sisters and I were growing up, we looked at these pictures as

slides he would project on special occasions. All of my early memories of Kentucky belong

to those slide shows.

I grew up in Southern California, living there from 1954 to 1958, then from 1961 to

1970. During the three years from 1958 to 1961, my father took us to Scotland where he

served a church of our denomination in Kirkcaldy, a linoleum factory town on the Firth of

Forth, an estuary of the North Sea. Those were important years, too, and I have written

about them in a number of poems, including those in my first book, North Sea, which

was published in 1978. Southern California is my landscape, however, and I think of Santa

Monica Bay and Redondo Beach, where my family lived, as the setting for many of my poems

and as the environment that most influenced me as a young writer.

Ironically, with regard to your question, I did reach back to my years teaching in

Murray, Kentucky to write my book-length poem Iris. Murray is on the western side of the state, and

Sharpsburg on the eastern side, and the regions are quite different. The area around

Murray is flat and agricultural, bounded on three sides by rivers and lakes; it is tobacco

and corn country. By contrast, Sharpsburg is hill country. I devote quite a bit to the

environment of Murray in Iris. I began the book here in Nashville and finished it

in England, where I taught for a year. It's a book about the South and about California.

The title character is based on my maternal grandmother, who was from Mississippi, and

some of my students at Murray State University. I am sure some of my parents' memories of

Sharpsburg made their way into the poem, too. But as you can tell, my environment has

changed often.

That is a long answer to your question. It is a curious phenomenon of American life

that we rarely grow up where we are born. I have always envied people who stayed put.

continued

|

|