| FEATURE |

|

Mark Doty |

|

Mark Wunderlich interviews Mark Doty |

Bruce Canwell |

|

Writers on Writing 5: It Takes All

Kinds |

R.T. Smith |

|

A Day in the Life of poet and editor R.T. Smith. |

|

|

|

Mark

Doty

|

|

Mark Doty is the author of four poetry collections,

the most recent of which is Sweet Machine, published in 1998 by Harper Flamingo,

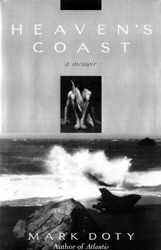

and the memoir Heaven’s Coast, which won the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for

First Nonfiction. He is the recipient of the Witter Bynner Prize for Poetry from the

American Academy of Arts and Letters, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los

Angeles Times Book Award, the T.S. Eliot Prize, has been a finalist for the National Book

Award, and has received numerous other grants and awards for his work. He lives in

Provincetown, Massachusetts and Houston, Texas, where he teaches at the University of

Houston. Mark Doty is the author of four poetry collections,

the most recent of which is Sweet Machine, published in 1998 by Harper Flamingo,

and the memoir Heaven’s Coast, which won the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for

First Nonfiction. He is the recipient of the Witter Bynner Prize for Poetry from the

American Academy of Arts and Letters, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los

Angeles Times Book Award, the T.S. Eliot Prize, has been a finalist for the National Book

Award, and has received numerous other grants and awards for his work. He lives in

Provincetown, Massachusetts and Houston, Texas, where he teaches at the University of

Houston.I conducted the following interview in November, 1998.

—Mark Wunderlich

|

|

| Interview

with Mark Doty |

|

Mark Wunderlich: In an article you published

in the Hungry Mind Review about your experience as a judge for the Lenore Marshall

Prize, you discussed your hopes for the future of American Poetry. I'm wondering if you

could talk a little more about that. Also, and this may be impossible to answer, but I'm

curious to know what vision you have for the future of your own work? What are your

current ambitions?

Mark Doty: I wrote the article you mention after reading a great many

collections of poetry publishing during 1996 and 97, and I wanted both to complain about a

certain tepidness in much of the poetry I was reading and to praise something else about

it, which I would describe as a kind of formal open-mindedness. This is something I've

been seeing increasingly as I travel and meet students in writing programs around the

country. It seems to me there is very little pure allegiance to one kind of practice, to

one school or another; the young writers I'm meeting want to forge a means of getting

their individuality on the page, and in order to do so they seem just as likely to write a

sonnet as they do a narrative poem, or a non-narrative piece with a less referential

quality. I think that's hugely exciting; the blurring of boundaries points towards larger

possibilities to come in American poetry over the next decade or three. I think we might

see fewer camps, and more individual, alchemical fusions of esthetic strains present in

our poetry now. That's my hope. And I fervently hope, too, that we will not settle for an

esthetic practice that leaves out the social and the political. I, for one, am hungry to

read poems of American life now, in all its messy complications, with its terrors and

uncertainties and possible grounds for hope.

Which leads me to the second part of your question, about my desires for my own work.

I've written a good deal, in recent years, along intensely personal lines. Those poems

move through my own experiences of grief to connect with readers' experiences of the

evanescence of what we love—or at least I hope they do! The work of the poet

investigating personal experience is always to find such points of connection, to figure

out how to open the private out to the reader. On one level, those were social and

political poems, since they deal with a highly charged, politically defined phenomenon,

the AIDS epidemic—or at least with the effects of that epidemic in my life. But the

poems go about that work in a personal, day-to-day way, more individual than global.

I'm wanting my own poems to turn more towards the social, to the common conditions of

American life in our particular uncertain moment. I am, I guess, groping towards those

poems; I'm trying to talk about public life without resorting to public language. I am

trying to address what scares and preoccupies me now. The project seems fraught with

peril—part of the reason we don't write political poems in America is that most of us

feel, well, what do I know? What authority do I have to speak? Where does my connection to

any broad perspective on social life lie? I don't see myself ever becoming a polemical

poet, or writing to advance a particular cause, but at the same time I can't believe that

it's okay for us to go on tending our private gardens while there is so much around us

demanding to be addressed.

I'd like to talk a little more about the notion of the political

in poetry. In what ways is a poem a suitable vessel for a political subject? What is it

that a poem can do with a political subject that another form of writing or discourse

can't? I suspect it may have something to do with the way in which poetry engages the

reader...

I've been talking about this a lot in print lately—in an essay in the Boston

Review this summer, which responds to Harold Bloom's introduction to the Best of

the Best American Poetry anthology, and in an argument-in-print with my friend J.D.

McClatchy, which will appear in the new incarnation of the James White Review this

winter. It occurs to me that my sense of what political poetry consists of is to some

degree generational; I'm young enough (or old enough, depending on your point of view) to

have been shaped by the notion that the personal is political. When I talk about

political poetry, I mean that work which is attentive to the way an individual sense of

identity is shaped by collision with the collective, how one's sense of self is defined

through encounter with the social world. Such a poem doesn't necessarily deal with, say,

the crisis in Bosnia or America's brutal mishandling of the AIDS epidemic, though it might

be concerned with these things. Though it does do more than occupy the space of the lyric

"I"; it is interested, however subtly, in the encounter between self and

history.

...we can have a queer interior,

which the outside world may not see, and so we begin to think about this difference

between the world of being and the world of seeming...

In this sense, many of the poems I love best are political poems. Bishop's "The

Moose", for instance, is a brilliant evocation of an experience in which an outsider,

defined by her separation from those perennial family voices droning on in the back of the

bus, suddenly has a mysterious experience of connection, of joining a community of

inarticulate wonder in the face of otherness. The isolation of the speaker in the proem to

"The Bridge" is not just an existential loneliness; he's waiting in the cold

"under the shadows of Thy piers" for a reason, which has to do with his position

as a sexual other. That the great steel rainbow of the bridge arcs over him there

is no accident; his otherness is an essential condition which helps to create the joy he

feels in the transcendent promise of the bridge.

What these poems can do which discursive writing cannot is dwell in that rich

imaginative territory of the interior connection, in imaginative engagement with the

troubling fact of self-in-the-world. I don't really believe there is such a thing as

"pure" esthetics; the esthetic is always a response, a formulation, an act of

resisting outer pressure, or rewriting the narratives we're given.

And you're right, it is about engaging the reader. Not with our opinions about things,

but with our felt involvement in the world, the self's inextricable implications with

culture and time.

I'd like to ask you about your work's relationship to

autobiography. Your poems are full of details of the lived life. They are poems of

intimacy, rather than ones that draw attention to the mask the poet wears. You also

published a very successful memoir about the loss of your partner, Wally, which is a very

frank meditation about a period of great personal difficulty. What are some of the

challenges presented by this kind of openness? What are its benefits?

I don't exactly feel that this openness has been a choice, although of course on some

less-than-conscious level it must be. Rather it feels to me as if it's simply the course

my life has taken, beginning in the early eighties with the process of coming out. I felt

then a great thirst for directness, an imperative to find language with which to be direct

to myself, which is of course the result of having been, like many young gay men, divided

from my self, from the authentic character of my desire. I felt I had to hide for years!

And the result of that for me, once I began to break through the dissembling, was a thirst

for the genuine.

And I like poems in which one gets the feeling of meeting a person; it's one of the

reasons I read poetry—for that experience of encountering another sensibility in its

context, a mind in its skin, as it were. So I would like my own work to be furnished with

the stuff of my life. There is an element of illusion to this, in that the self on the

page is always a construction; one can't put all of oneself on paper; there are always

contradictions, divergences, complexities. Thank goodness! Any poem creates an

"I", a character who is its speaker, and on one level this creation is always a

performance; one shouldn't mistake the authenticity of art for the facts of autobiography,

necessarily! I am interested in getting at something with the feeling of the lived life on

the page, and that often involves rearranging the facts, compressing,

heightening—lying, if you will. That said, I don't really make much up; my

imagination's fired more by trying to limn what is!

There is an esthetic risk to this, of course, which is that what feels deeply resonant

to the maker, who knows the context of his tropes, may not carry such a charge for the

reader. The more immediate our investment, the harder it is to find the degree of distance

the poem requires. To some extent, that's what the composing process is:

discovering the degree of distance at which we can stand in order to make our emotions and

experiences available to the reader.

And there's a funny personal risk, too, which is the oddity of discovering that people

who I don't know sometimes know me, at least in a way; if the reader's entered

deeply into a book, she or he may feel profoundly intimate with the author. And, in a way,

they are, though on a more worldly level, they aren't at all. I have sometimes found this

jarring, but I have to remember that it is a great compliment. I have felt this way myself

with writers whose work I love. When I first met James Merrill I felt deeply confused,

because I seemed to know him intimately, though of course what I knew was the Merrill of

the books, and how startling it was NOT to know the man!

One last note about

this. When Heaven's Coast came out, I went through a terrible (and fortunately

brief) period of feeling that I had turned my memory into a book; that there was nothing

left of my relationship with Wally except what I'd turned into stories. I felt bereft for

a while, until I remembered something which I'd left out of the book, which felt like such

a gift—the returning awareness that my life was larger than the story I'd made of it,

that it resisted being reduced to a single narration. One last note about

this. When Heaven's Coast came out, I went through a terrible (and fortunately

brief) period of feeling that I had turned my memory into a book; that there was nothing

left of my relationship with Wally except what I'd turned into stories. I felt bereft for

a while, until I remembered something which I'd left out of the book, which felt like such

a gift—the returning awareness that my life was larger than the story I'd made of it,

that it resisted being reduced to a single narration.

I understand you're working on a new memoir. How does this one

differ from Heaven's Coast?

I've finished it, actually. The new book's called Firebird and will be out from

HarperCollins next year. It is a very different book than Heaven's Coast which was

more meditative, nonlinear, and drew at least part of its form from the journal (though it

also has elements of nature writing and literary criticism, but that's another story). Firebird

is an autobiography from six to sixteen, with a particular eye towards matters of esthetic

education: How do we learn to identify what we find beautiful, and what are the uses to

which beauty is put? It's a sissy boy's story, and thus an exile's tale, and a chronicle

of a gradual process of coming to belong somewhere, to the world of art.

The book is formally quite different, in that it behaves more like a novel—a

continuous narrative which traffics less in reflection and discursive writing and more in

scene and in character. Its project is to place the self in context, to think about my own

peculiar family and about American life in the fifties and sixties. I hope the book is not

so much about me as it is an examination of a whole constellation of experiences and

ideas—personal and collective—about art, sexuality, identity, gender, and the

survival of the inner life.

continued

|

|