|

Introduction by Ginger Murchison

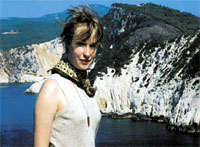

Alicia is visiting Atlanta from her current home in Athens,

Greece. Although perfectly fresh and vibrant, she has a terrible

sinus infection, so I brew some hot tea, which I hope will be

soothing. Waiting for the tea, she surprises me with the gift of a

hand-painted ornamental plate she's brought from Greece. I thank

her, we take the tea things into the study, settle into a

comfortable spot in front of the fireplace, and begin to chat about

her impressive first book, Archaic

Smile.

—Ginger Murchison

The Interview with A.E.

Stallings

TCR: Alicia, this is just a stunning

book.

AES: They did a very nice job.

TCR: I must say that

when I pick up a book of formal poetry written by someone trained

in the classics, I don't expect to find a lot of humor, but one

of the things so special about this book is its freshness, and I

don't limit that freshness to newness. There's

another kind of freshness here, a cheekiness, and part

of the surprise is in the perspectives you take. We're familiar

with your subjects; many of them are

Olympians––inaccessible, unapproachable––yet

because of your perspective, it's almost as if we've caught a

goddess hiking up her pantyhose. How did you come to that? And

that was a very long question. I'm sorry.

AES: One thing about studying the

classics is that you realize there is no one version of a

myth. Bullfinch's Mythology tells us there

is a myth, but that just isn't true. Homer may have one

version, Ovid another version; Virgil still another version,

and the classical authors clearly felt free to change the

myths to suit their own purposes. They didn't consider them

cast in stone or untouchable, so you get the impression you

can be free, too, to do with the characters what you want to.

Sometimes when I want to write something personal, I'll write

through a persona; then it's neither personal nor mythical,

and it sort of becomes a combination of the two things, and

if I'm trying to write about the myth, I'll deliberately

search for a wholly different point of view because the

traditional one doesn't make for a very interesting poem.

TCR: It's that

freshness, no doubt, for which this book got so much attention.

It won the Richard Wilbur award, judged by Dana Gioia, but was

short-listed for several others, right?

AES: Yes. [Laughing] It was short-listed

many, many times: short-listed for the Yale Younger Poets

Award three times and the Walt Whitman Award three times; and

lots of other ones, too.

TCR: It must have been

terribly exciting to get all that response to your first book.

AES: At first, yes, but then I just

thought I was going to be a permanent finalist. [Laughing]

Actually it's a real honor to be a finalist, but what I don't

like about some of the contests—the Yale Younger and the

Walt Whitman are both examples—is that they send you a

"Congratulations-you-may-have-won" letter telling

you you're a finalist, and you have to live with that for

three months until the winner is announced. This is terrible

for everyone. You are on tenter-hooks for all those months;

then you lose. I'd much prefer to find out that I didn't win,

but that I was a finalist. It was nerve-wracking, but it was

definitely encouraging.

TCR: …and you've

won the James Dickey award.

AES: For two poems, yes, that I published

in Five Points.

TCR: …and the

Pushcart Prize, and the Eunice Tietjens Prize from Poetry

Magazine.

AES: Yes, I feel pretty lucky.

TCR: I just want to

turn you loose here to talk about your childhood, your family,

your early schooling and whatever you think specifically might

have prepared you to become a poet.

AES:

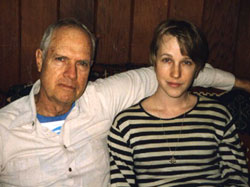

I think it was an unusual childhood. My father, who was a

professor at Georgia State, was both intellectual and

outdoorsy; so he could discuss Proust or skinning deer, and

we, my sister Jocelyn and I, grew up, not exactly tomboys,

but I did know how to gut a fish when I was four. I think my

parents had a theory that children should be treated as if

they had no gender. We had a workbench for carpentry, and we

played with dolls. Well, we were actually forbidden to play

with Barbie dolls, but we weren't really interested in

Barbie, anyway. AES:

I think it was an unusual childhood. My father, who was a

professor at Georgia State, was both intellectual and

outdoorsy; so he could discuss Proust or skinning deer, and

we, my sister Jocelyn and I, grew up, not exactly tomboys,

but I did know how to gut a fish when I was four. I think my

parents had a theory that children should be treated as if

they had no gender. We had a workbench for carpentry, and we

played with dolls. Well, we were actually forbidden to play

with Barbie dolls, but we weren't really interested in

Barbie, anyway.

TCR: I have to

interrupt already. In your poem "Ariadne and the Rest,"

you talk about what makes girls feminine. Nursery rhymes, you

say, were concocted

To beguile the little girls indoors,

To keep them out of fights, discourage

Curiosity in swords, to keep them still

While nurses yanked out knots from tangled curls.

So I got the idea that maybe

you had that kind of sculpted, sweetly protected childhood.

AES:

No, no. My parents didn't actually believe in the gender

thing, but I think maybe we were interested in it anyway,

partly because we saw others being happy with that and partly

because our parents didn't seem interested in it, but we were

read to: all kinds of things. I always liked the fairy

tales—the original, uncut versions, the ones with

violent, horrible endings. I think the unexpurgated fairy

tales are actually comforting to children. They are a lot

more cathartic. I mean something happens to the bad people,

and they get put away, so you feel safe when the story is

over. I never remember having a nightmare because of a fairy

tale, and I liked Hans Christian Anderson's tales. They often

have sad endings. The Little Mermaid, for instance,

has a very sad ending. AES:

No, no. My parents didn't actually believe in the gender

thing, but I think maybe we were interested in it anyway,

partly because we saw others being happy with that and partly

because our parents didn't seem interested in it, but we were

read to: all kinds of things. I always liked the fairy

tales—the original, uncut versions, the ones with

violent, horrible endings. I think the unexpurgated fairy

tales are actually comforting to children. They are a lot

more cathartic. I mean something happens to the bad people,

and they get put away, so you feel safe when the story is

over. I never remember having a nightmare because of a fairy

tale, and I liked Hans Christian Anderson's tales. They often

have sad endings. The Little Mermaid, for instance,

has a very sad ending.

My mother was a school librarian, so there were

always books around the house, and the shift into reading on

my own was natural. Every week we took a laundry basket to the public

library and filled it up, so there was a lot of reading�.

I was aware, too, from a very early age that

books were written by people and that one could be a writer,

and I wanted to write books. My mother encouraged me, and

since I expressed an interest, my dad would take me out of

school to hear a speaker at Georgia State, Eudora Welty at

Agnes Scott, Stephen Spender, all kinds of writers, so I was

always aware of people who were writing.

I went to Briarcliff High School that closed

shortly after I graduated, but I got a really good education

there. It was on the verge of being shut down because the

area had gotten older and there weren't many kids in the

neighborhood, so we had a small student-teacher ratio, and

people with Ph.D.'s were teaching at Briarcliff. We had an

excellent English teacher, but a terrible football team.

[Laughing]

Since a lot of Emory, Georgia Tech, and Georgia

State professors lived in the area, quite a lot of the

students were children of professors. For that reason, I

guess, there was a significant group of unusual kids; we had

our own in-group of geeks, I guess. [Laughing]

TCR: Had you found

poetry by this time? Do you remember the first time you were

fascinated by a poem?

AES: There are actually two or three of

those moments. My parents, though big on reading, were not

particularly interested in poetry, though my father, like a

lot of people of that generation, grew up with Longfellow. It

was maybe a generational thing, but he could quote long

passages and would on occasion, but he didn't have an

interest in keeping up with contemporary poetry. I remember

at about 8 or 9 being really fascinated with William Blake's

"Tiger, Tiger," partly because I was obsessed with

tigers—one of my phases—and I wrote a poem in

imitation. I don't remember the poem except that it was

extremely close to the original.

And then when I was about 13 or so, I was at my

grandparents'. It was one of those long Sunday afternoons,

and we'd run out of things to read. I went through the books

on the shelf and opened T.S. Eliot's "The

Wasteland" to the section where a woman is brushing her

hair, and Eliot mentions the baby-faced bats and the strings.

I had no idea what it meant, but I thought it was really,

really cool, and I remember being fascinated by T.S. Eliot

after that, not from any kind of intellectual comprehension,

but I thought the sounds were really neat.

So I was attracted initially by rhythms.

"Tiger, Tiger" is in that strong trochaic

tetrameter—most nursery rhymes are—that is very

appealing to children. It was purely the music that drew me

to T. S. Eliot. Later, I would try to do term papers and

understand him. Even now, though, I think there is too much

energy put into attempting to understand Eliot. He even talks

about "The Wasteland" as being "rhythmical

grumblings."

TCR: …and then

college at the University of Georgia?

AES: Yes. I was an English and music

major. I'd read in English, and I'd run into this Latin

phrase and that classical allusion, and there'd be a

footnote, and it occurred to me that I needed to, as it were,

get me some Latin [Laughing], so I took a Latin class from a

wonderful professor, Dr. Harris, a legend at the University

of Georgia, and it was such a wonderful class that I changed

my major. My father wanted me to take Latin in high school,

which seemed to me a good reason to take Spanish—a

teenage thing—so he was pretty amazed when I changed my

major.

I'd always enjoyed the classical myths, maybe

from my early love of fairy tales, but it became more and

more clear to me that the English poets whom I admired had

actually studied the classics and not English, which wasn't

even a discipline then , so I guess that seemed to me a good

path to follow.

TCR: Were you writing

poetry by then? Had you attempted to publish anything?

AES: Actually, I was kind of lucky. I had

published some poems in high school. While it was lucky for

me at the time, I'm not sure it was good for me. I published

some poems in Seventeen, some other magazines, even

some literary magazines. I think the first poem I sent out

got accepted, and I got a check and I thought, WOW! this

is my big career, easier than babysitting, and obviously

I was completely misled. [Laughing]

Later on, in college, I had the attitude...Oh,

well, I've been published in all those magazines, I'll try

these bigger, better ones, and of course, I got my

reality check.

TCR: So, Dr. Harris led

you to study Latin. Can you credit anyone in particular with

leading you to write poetry?

AES: I had a very good—a very, very

good—AP English teacher at Briarcliff, Mary Mecom, who

recently passed away with cancer. We didn't study poetry

writing; the class was about reading, but I think they're

really flip sides of each other: reading is about writing and

writing is about reading, so class with her was very helpful.

It was a very intensive AP class with Perrine's Sound

and Sense, which is a wonderful book. I guess we

did a sonnet or something like that in class, and I published

some poems in the high school literary journal. Mary Mecom

definitely helped in terms of writing.

TCR: I'm sorry she

can't hear you say this. Did she know before she died that you

were writing, knocking down all these poetry awards?

AES: I didn't speak to her again

personally, but I did write her several letters. When I first

got into Best American Poetry, I sent her a copy.

TCR: …and after

the University of Georgia?

AES: I lived in London for a year and

worked at The Institute of Classical Studies as the canteen

manager: I was "the tea girl." The director there

encouraged me to apply to Oxford for graduate school. I

stayed, then, for graduate school and studied Latin and

Greek. I met my husband there.

TCR: Your husband is

Greek…John Psaropoulos, who edits the Athens News.

AES:

Yes, he'd gone to boarding school and university in England,

and he was working on a masters in classics at The Institute

for Classical studies where I was the tea girl. While I was

at Oxford, he stayed in London; then we both moved to

Atlanta; then we married and moved to Greece. AES:

Yes, he'd gone to boarding school and university in England,

and he was working on a masters in classics at The Institute

for Classical studies where I was the tea girl. While I was

at Oxford, he stayed in London; then we both moved to

Atlanta; then we married and moved to Greece.

TCR: OK, here's where I

have to ask you about "A Postcard from Greece," the

incredibly stunning opening poem in Archaic Smile. Is it

really autobiographical?

AES: Yes, although I take some

poetic license and adjust a fact or two. My husband feels his

driving is impugned in the poem [Laughing] , but we did

hit an olive tree. Apparently, lots of lives have been saved

by that particular tree—it has a huge dent in

it—but I guess I should mention that John doesn't feel

the event happened precisely that way.

TCR: Whether it did or

not, it's perfectly clear that something pretty traumatic is

going on in you.

AES: It was traumatic for John, too.

Although he'd grown up in Greece and lived there at different

times, he hadn't lived there for a long, long time. We'd both

quit our jobs, sold pretty much everything we owned, left our

friends and my family here, and took this huge cultural leap.

It was a traumatic uprooting; very sudden.

TCR: What's a typical

day in Greece like?

AES: John's days are much more typical

than mine. He's very busy at the paper. I'm either taking

Greek classes or I'm at the American School Library working

on my translation, but in Greece, everything takes

time—grocery shopping, paying bills—there's more

bureaucracy, so it's really helpful that one of us is not

working.

TCR: Some women poets

say their husbands, though outwardly supportive, resent the

isolation poetry requires. Does John resent, at all, the time you

spend on your writing? You're both educated in the classics, so

in some ways that might unite you, but in other ways, does your

writing strain your relationship?

AES: Not really. He works twelve hours a

day, and he's very supportive. He's my first reader.

TCR: Your husband is

your first reader?

AES: I think that's a lot of pressure.

I've been sitting home all day; he walks in and I say,

"I have a poem." If he doesn't like it, we'll have

a fight, then I'll change everything. [Laughing]

Very occasionally, I disagree. Well, I always

disagree at first, you know, because, of course, it's

brilliant work [Laughing], but he's right ninety-eight

percent of the time. He knows my work very well, so he also

knows when I'm at the top of my form. He has a very good

natural ear, so if meter is a problem, he points that out, or

if a rhyme is weak, he sees that.

TCR: Was writing in

form, by the way, a conscious decision made somewhere along the

course of your studying the classics?

AES: No. I started out writing in form;

it comes naturally to me. I went through a phase where I was

really interested in T.S. Eliot, and I was trying to write

like that—really exploded form. Those poems sort of look

like free verse, but they're heavily iambic with a lot of

internal rhyme. Because I didn't think you could publish

formal poems—I mean it wasn't a good time for formal

poetry in the magazines—and I really did want to

publish, I tried for a while to write free verse, and I went

through this long, dry spell where I didn't publish anything.

When I went back to submitting poems, oddly enough, it was

the formal poems that were accepted, even by the mainstream

journals, so I realized that's what I should be doing, and I

gave up experimenting in free verse.

TCR: It's true. Form

doesn't seem to inhibit you at all. You're one of the few people,

I think, who can make a formal poem conversational.

AES: Obviously I work at the edges,

revise a lot, but I don't sit there and scan lines. It pretty

much comes. The rhythm is very natural to me. That's not a

very interesting answer, I know, and I fought it for a long

time, maybe because when something comes easily to you, you

value it less or feel it should be more difficult, but I

really did struggle writing dreadful free verse for a long

time.

TCR: The fact that you

feel more free than bound by form is an interesting one. I found

an essay of yours on the Internet—I don't remember

where—titled "Crooked Roads Without Improvement: Some

Thoughts on Formal Verse." In it you say, "to rule out

meter or rhyme as tools available to the poet is far more

limiting than the playful, silk-ribbon bondage of the

sonnet." Would you elaborate on that for TCR readers?

AES: The truth is that prose

has access to all the rhetorical devices available

to poetry—metaphor, anaphora, simile, you name it—except

the line as a unit, and except for regular meter and

rhyme. Those are some of the most powerful tools in the

poet's kit. To arbitrarily say I'm never going to use those

things seems as absurd to me as a painter deciding he will

only paint in black and white. Why not use these

great tools? What could be more fun than playing around with

rhyme? And people love rhtyme. Rhyme and meter make things

memorable. And that's a physical thing—they work

differently upon the brain, I'm sure of it. Form opens up all

kinds of possibilities. Rhyme often leads you to write things

that surprise you. A meter may help you tap into a forgotten

emotion. With form, certain decisions have already been,

arbitrarily, made for you—a certain number of lines, a

designated meter with a particular pattern of rhymes. That

frees you up to think about other, more interesting choices

in the poem.

TCR: In further defense

of form in that essay, you say, "the way literature classes

are taught, with developments in a chronology, imples that there

is some sort of progress in literature, but this is an illusion.

There is change, yes. Progress, no." I like your argument

here. Would you reiterate it for TCR?

AES: Of course there is change,

even innovation. But poetry does not evolve towards something

better. It goes in cycles. Golden ages are followed by silver

ages, not the other way around. There is nothing in Western

literature greater than Homer, and he marks the very dawn of

our literature. To be honest, I also find this freeing. I am

not concerned with the pressure to be original, which, more

often than not, leads to novelty rather than innovation. And

nothing gets old faster than novelty.

TCR: I know you're a

friend—at least an acquaintance—of Turner Cassity's.

Turner calls you a "born technician." He argues, by the

way, that that's not an oxymoron. Do you feel like "a born

technician"?

AES: I do enjoy playing with the

technical aspect of poetry, and inasmuch as I feel very much

at home with form and meter, I guess I could be because a lot

of it is not all that conscious. It's there, but most of the

time I don't see it until later.

TCR: When you are

writing in form, are you religious about it, or do you break the

rules? [Laughing] I think I know the answer to this already.

AES: There are formalists, actually, who

object to a lot of the book, who feel that I take too many

liberties with metrical substitutions; I have some

heterometic poems where lines are longer or shorter than how

they start out. I've got a poem in there that looks like a

villanelle but isn't a villanelle. Form is just a tool,

another way to get where you're going, and you should be able

to use it any way you want to. Maybe I should feel more

reverent about it, but poets in the past pretty much used

form however they wanted to. Shelley's "Ozymandias"

is a sonnet with a nonce rhyme scheme, so I feel pretty free

to do whatever I want.

TCR: Do you decide on

the form before you start to write, as in, "OK. I'm going

to write a sestina"?

AES: No, I don't get very far with a poem

until I've got a first line, and I don't find out what it's

going to be until I get the first line.

TCR: You have to have

the first line? [Laughing] Those just pop out in the dark?

AES: [Laughing] Pretty much. I might have

an idea for a poem, but unless I've got a first line, I can't

get into it. The first couple of lines suggest the form. If I

sit down and say I'm going to write a sonnet, that's usually

purely an exercise when I'm having a hard time writing

anything, and that usually doesn't result in much, so it's

usually the first couple of lines in a poem that suggests

something. For instance, if there's an immediate repetition

in the first couple of lines, I think: maybe this is headed

toward a villanelle. If it's going to be a fairly short poem

in iambic pentameter, then I start thinking: maybe it's a

sonnet. Most of my sonnets are either 12 or 16-line poems

that I decided were actually pretty sonnet-like, and I just

reinforced that form by taking out lines or seeing where I

could fill it out. The first line really tells me a lot about

the poem. If it's about a character, that character's whole

voice will be in the first line. I don't think any of my

poems ever got written and then the first line added. The

poem dictates.

The nice thing about form and especially about

rhyme, however, is that rhyme schemes often tap into the

subconscious because a word will suggest itself, in fact a

whole line will suggest itself in a rhyme scheme that you

would not have thought of, and you wouldn't have expected

that's where the poem was headed. The word or line was

suggested because it rhymes, yes, but looking for that rhyme,

you tapped into a different level of your thoughts, and when

that happens, you write something quite surprising.

TCR: That shows up, I

think, because the formalism is in striking contrast with the ordinariness

of your characters. Is that a contrast or counter-weight you go

after deliberately, or does that just happen because you know the

myth doesn't have to be strictly adhered to?

AES: I think you'd achieve a certain

amount of sterility if you were working in traditional forms

and writing about high-falutin subjects in elevated language.

You'd just be regurgitating Victorian literature, and you

wouldn't be getting at anything new. I guess I do enjoy

contrasts. I enjoy throwing a very colloquial word into a

sonnet. [Laughing]

TCR: Who's your

favorite poet, then, who writes in form?

AES: Among the living poets, my favorites

are Richard Wilbur and Seamus Heaney, but my favorite poet is

probably A.E. Housman, and I love Thomas Hardy, Wilfred Owen,

all the Georgian poets, basically. I feel descended more from

them, I guess, than the modern poets.

TCR: And what

non-traditional contemporary poets do you read, or do you even

feel comfortable in a poem that doesn't have a traditional

structure?

AES: Yes, I do. Like I said, I had an

early love affair with T. S. Eliot. I read a lot of poetry,

and I like the modernist poets a lot, but I guess I would say

this: strictly free verse poetry requires a lot of tension

and skill to carry off. I like the poets who tread a thin

line between form and free verse or who early-on were formal

poets and then went to free verse because I think they are

the ones best able to maintain that discipline and tension.

So I like of lot of James Dickey's early work. I like a lot

of Roethke. This is what I like about Seamus Heaney, for

instance. He does a lot of formal poetry, and he does a lot

of free verse, but his free verse maintains that tension,

that discipline. I like to feel that tension. I think free

verse is sometimes chopped-up prose.

TCR: Another question

or two about Archaic Smile, then I'm going to ask you to

read from it. I'm curious how you came about the title and the

cover. The cover, by the way, is exquisite.

AES: John picked out the photograph. I

probably would have picked out a photograph with more of an

archaic smile on it, but I think it's a beautiful

kore—the kore are ancient statues of women, usually

Persephone, and most of them have significant damage to the

face, but this is a very nice one, and you can still see some

of the paint. Of course, ancient sculptures were a lot more

garish than we think they were. As for the title, the book

had gone through all kinds of titles, and nobody liked any of

them. This one just came to me one day, and everyone was

happy after that.

TCR: It's clear you've

taken a hard look at these mythical figures and become completely

comfortable with them, and it's that intimacy that creates the

fun, the archaic smile. It's understandable you could get

familiar with Persephone, perhaps, but the demons? You say

they're "more beautiful than the angels" because

"they had no qualms about plastic surgery," and

"their complexions were so pale/ The blonde looked natural,

only more so." How did you get permission to take such

liberties with demons?

AES: I think I find the pagan concept of

the underworld and afterlife almost more believable—more

human—than the Christian heaven and hell thing, which

seems like an immense abstraction very difficult to picture,

but the pagan underworld is really under the world;

it's a physical place with physical rivers and geography.

Maybe it's a combination of having visited Mammoth Cave as a

small child and having read those fairy tales like The

Little Mermaid. Remember, she goes down to the sea

witch's house. Certainly there are wonderful descriptions in

Virgil, in book 6 of the Aeneid, for

instance, where the underworld is really very realistic, and

when Aeneas, who is a living person, crosses into the

underworld, he has to take the little boat, the ferry, across

the River Styx, and, of course, they're all ghosts getting

carried on this leaky boat, but Aeneas is a living person, so

when he steps in, the whole boat sinks over in his direction,

and water comes up through the planks. It's these wonderful

early descriptions that seem so very real to me and make

Hades a real place.

TCR: This would be a

good place for me to ask you to read "Persephone Writes a

Letter to her Mother." Would you mind?

AES: Of course not.

Persephone Writes a

Letter to Her Mother

First—hell is not so far underground—

My hair gets tangled in the roots of trees

& I can just make out the crunch of footsteps,

The pop of acorns falling, or the chime

Of a shovel squaring a fresh grave or turning

Up the tulip bulbs for separation.

Day & night, creatures with no legs

Or too many, journey to hell and back.

Alas, the burrowing animals have dim eyesight.

They are useless for news of the upper world.

They say the light is "loud" (their figures of speech

All come from sound; their hearing is acute).

The dead are just as dull as you would imagine.

They evolve like the burrowing animals—losing their sight.

They may roam abroad sometimes—but just at night—

They can only tell me if there was a moon.

Again and again, moth-like, they are duped

By any beckoning flame—lamps and candles.

They come back startled & singed, sucking their fingers,

Happy the dirt is cool and dense and blind.

They are silly & grateful and don't remember anything.

I have tried to tell them stories, but they cannot attend.

They pester you like children for the wrong details—

How long were his fingernails? Did she wear shoes?

How much did they eat for breakfast? What is snow?

And then they pay no attention to the answers.

My husband, bored with their babbling, neither listens nor

speaks.

But here there is no fodder for small talk.

The weather is always the same. Nothing happens.

(Though at times I feel the trees, rocking in place

Like grief, clenching the dirt with tortuous toes.)

There is nothing to eat here but raw beets & turnips.

There is nothing to drink but mud-filtered rain.

Of course, no one goes hungry or toils, however many—

(The dead breed like the bulbs of daffodils—

Without sex or seed—all underground—

Yet no race has such increase. Worse than insects!)

I miss you and think about you often.

Please send flowers. I am forgetting them.

If I yank them down by the roots, they lose their petals

And smell of compost. Though I try to describe

Their color and fragrance, no one here believes me.

They think they are the same thing as mushrooms.

Yet no dog is so loyal as the dead,

Who have no wives or children and no lives,

No motives, secret or bare, to disobey.

Plus, my husband is a kind, kind master;

He asks nothing of us, nothing, nothing at all—

Thus fall changes to winter, winter to fall,

While we learn idleness, a difficult lesson.

He does not understand why I write letters.

He says that you will never get them. True—

Mulched-leaf paper sticks together, then rots;

No ink but blood, and it turns brown like the leaves.

He found my stash of letters, for I had hid it,

Thinking he'd be angry. But he never angers.

He took my hands in his hands, my shredded fingers

Which I have sliced for ink, thin paper cuts.

My effort is futile, he says, and doesn't forbid it.

TCR: There's a good bit

of death in your poems, but no morbidity. You call death the

"deportation officer," describe it as "clarity of

mind," and in the poem, "Elegy for a Loggerhead

Turtle," you say the turtle is "a broken time

machine," a "shipwreck…washed up on Death, that

long, dry land." Later, in "A Lament for the Dead Pets

of Our Childhood," death is a "cold thing in the image

of a warm thing,/ Limp as sleep without the twitch of

dreams." Death and the underworld seem more euphemistic,

then, than morbid, more about change than loss, with a definite

fairy tale aspect—that's a warm-hearted way of looking at

it.

Which poem in Archaic Smile

do you enjoy reading most?

AES: I really enjoy reading the Willow

Tree poem because it's very accessible and people seem to

enjoy it.

TCR: I've heard you

read that, and you're right. The audience loved it. Would you

mind?

AES: Not at all.

The Man Who Wouldn't

Plant Willow Trees

Willows are messy trees. Hair in their eyes,

They weep like women after too much wine

And not enough love. They litter a lawn with leaves

Like the butts of regrets smoked down to the filter.

They are always out of kilter. Thirsty as drunks,

They’ll sink into a sewer with their roots.

They have no pride. There's never enough sorrow.

A breeze threatens and they shake with sobs.

Willows are slobs, and must be cleaned up after.

They'll bust up pipes just looking for a drink.

Their fingers tremble, but make wicked switches.

They claim they are sorry, but they whisper it.

TCR: That freshness

comes to your poems in so many ways, and here it's apparent in

the repetition of sounds. You play on our sentimentality with

"they shake with sobs," then follow immediately with

the starkly unsentimental, "Willows are slobs,"

laughing at us, almost, for falling for it. It would be

impossible to miss the fairy tale quality in that poem. It's

clear that you are not a morose person.

AES: [Laughing]

TCR: One of my

favorites is "Cardinal Numbers." I can almost visualize

children skipping rope to this, and I'd love our readers to hear

it in your voice. OK?

AES: Certainly.

Cardinal Numbers

Mrs. Cardinal is dead;

All that remains—a beak of red,

And, fanned across the pavement slab,

Feathers, drab.

Remember how we saw her mate

In the magnolia tree of late,

Glowing, in the faded hour,

A scarlet flower,

And knew, from his nagging sound,

His wife foraged on the ground,

As camouflaged, as he (to us)

Conspicuous?

One of us remarked, with laughter,

It was her safety he looked after,

On the watch, from where he sat,

For dog or cat

(For being lately married we

Thought we had the monopoly,

Nor guessed a bird so glorious

Uxorious).

Of course, the reason that birds flocked

To us: we kept the feeder stocked.

And there are cats (why mince words)

Where there are birds.

A 'possum came when dusk was grey,

And so tidied the corpse away,

While Mr. Cardinal at dawn

Carried on,

As if to say, he doesn't blame us,

Our hospitality is famous,

If other birds still want to visit,

Whose fault is it?

TCR: How can any reader

not revel in a rhyme like "glorious/uxorious." The poem

has its dark side, but it's still fun.

AES: A huge number of fairy tales and

nursery rhymes have dark sides, and we do a disservice to

Disneyfy everything for kids. Children are aware that bad

things happen, that people die and animals die, and when

that's incorporated into something like a story or a poem,

where it's put into some sort of order, where it's

controlled, it becomes less threatening, and they know

they're dealing with the truth, that we're not hiding things.

But when death isn't mentioned at all, when the monster is

only a monster because he is lonely and wants to make

friends, we offer a false sense of security. In fact, it

doesn't tangle with any of their real concerns; it's a

completely false world. I think it's nice to bring the real

world into something controlled like a story and a poem.

Giving up something, a character, an animal in a story or

poem, is practice for giving up something closer later.

TCR: So what is next

for AE Stallings?

AES: My main project right now is a

translation of Lucretius' De Rerum Natura [On the

Nature of things] for Penguin Press. It's about the atomic

theory. That makes it sound dull, but it's really a wonderful

poem, and I'm translating it into verse. I'm about halfway

through.

TCR: Why did you choose

a translation? Won't a translation quiet that imp in you?

AES: I think it does actually.

Translation is a different process, but you are using the

same skills and creativity, not with your own words, your own

ideas; it's just a very different kind of process. I have

been writing, at the same time, of course, my own poems, but

the translation is taking up most of my energy right now. On

the other hand, since I'm in Greece and don't have a job

right now, it gives structure to the day. I'd probably be

writing more poems if I weren't doing the translation, but it

will obviously enrich me in other ways.

TCR: Are you letting

some of your light spirit get into that work?

AES: Yes, I think so, because the

original is in unrhymed dactyllic hexameter, and I'm doing it

in rhyming fourteeners, which is a very rambunctious meter,

and I'm having a lot of fun with the rhymes, so some of me

gets through, too. It has its own light touches, and it's a

poem I'm sort of well suited to in several ways. Even though

in theory it's this sort of dry text explaining atoms and

Epicurean philosophy, Lucretius explains things in wonderful

vignettes. There's a wonderful passage where Lucretius is

talking about the evils of religion, but it's about a cow

whose calf has been taken for sacrifice, and the cow wanders

over the meadow and back to her stable, mooing for her lost

child, mooing that no other calf can replace it. It's

beautiful and at the same time whimsical because there's so

much personification lavished onto a cow. It's full of

interesting touches like that with a lot of whimsical

aspects, even very funny ones.

TCR: Did you choose

that project and take it to Penguin or did they offer it to you?

AES: It was strange. I had translated the

first book—it's an epic poem in six books—as a

lark. My former tutor at Oxford knew about it, and someone

from Penguin approached him, saying they were looking for

translators, and he mentioned I was working on Lucretius. I

really didn't think it would fly. I mean I didn't think

Penguin would want a rhyming Lucretius, but they thought it

was fun, so we'll see.

TCR: So, will we see

another collection like Archaic Smile after you finish De

Rerum Natura?

AES: I actually have quite a few new

poems, but I'm not planning to have another book out for four

or five years. I was very happy with this book because while

I was waiting to publish it, I kept taking poems out and

putting poems in. That was really good for me and good for

the book, and although I'll probably have enough poems for a

book in a year, I'm not in any rush about publishing another

one.

TCR: Before we finish,

I'm going to look up one of my favorites, "The Dogdom of the

Dead," and see what first line just popped out in the

dark…. "There is no dog so loyal as the dead."

That line just popped out in the dark?

AES: Well, that one is interesting.

[Laughing] That line actually occurs in the Persephone poem

(slightly differently), but I liked the line, so I decided to

write a separate poem with it.

TCR: [Laughing] At

least you're smart enough to steal from a really fine poet! You

are going back to Greece in a few days. You've been gone two

years now. What shocks you most when you come back?

AES:

The sheer glut of products in the grocery store that

people do not need. The consumerism is almost

obscene… and being able to buy strawberries only in

season has its advantages; it means that they are a surprise

every year. AES:

The sheer glut of products in the grocery store that

people do not need. The consumerism is almost

obscene… and being able to buy strawberries only in

season has its advantages; it means that they are a surprise

every year.

TCR: And what will you

take back with you?

AES: I'm not sure yet. Grits!

TCR: GRITS!?!

AES: Yes, grits, and hot sauce. Maybe

maple syrup. We can't get black beans there, either.

TCR: [Laughing] Alicia,

you are as much fun to talk to as you are to read, and The

Cortland Review is happy you've become part of its family.

Best of luck with your translation of Lucretius, and feel better.

Ginger Murchison traded

her teaching career for time to write and enjoy

poetry in 1997. She is published in several small

press magazines and anthologies, including Touched

by Adoption (Green

River Press, 1999) and, most recently, Intimate

Kisses (New World

Library, 2001). She divides her time between Atlanta,

Georgia and Sanibel Island, Florida. She is the

Assistant Managing Editor of The Cortland Review.

|