It sounds bad, you playing husband,

playing father, you playing the man

who starts to believe

the words on his business card,

putting on your suit in the morning

the way knights once put on their armor,

all day carrying a heaviness

that at first gets you down, yet soon

begins to feel normal, a chosen

weight, your very own masquerade.

It sounds bad, but you've tried hard

to successfully impersonate that man.

You've wanted act to become habit,

love replicated to be a definition of love,

though in fact you've been an impostor

of an impostor, often able to manufacture

authenticity when you've needed to,

then observing its effect. But consider

what used to sound good—someone

earnestly trying to be himself,

as if being oneself couldn't be hideous,

you and people you've known:

pigs in the slop, men in the throes

of discovering the joy in their malice.

-

Winter Feature 2010

-

Feature

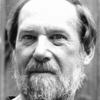

- Poets in Person An HD video visit with Stephen Dunn in Frostburg, MD

-

Poetry

- Jonathan Aaron

- Michael Blumenthal

- Billy Collins

- Philip Dacey

- Carl Dennis

- Gregory Djanikian

- Stephen Dobyns

- Stephen Dunn

- B.H. Fairchild

- Kathleen Graber

- Jane Hirshfield

- Tony Hoagland

- Dorianne Laux

- Thomas Lux

- D. Nurkse

- Alicia Ostriker

- Lawrence Raab

- J. Allyn Rosser

- Dave Smith

- Gerald Stern

- Ellen Bryant Voigt

- C.K. Williams

- Robert Wrigley

-

Essay

- Gregory Djanikian Stephen Dunn's Compositional Strategies: Verse And Reverse

- David Rigsbee The Despoiled And Radiant Now: Ambivalence And Secrets In Stephen Dunn

-

Book Review

- David Rigsbee reviews Here and Now: Poems

by Stephen Dunn

- David Rigsbee reviews Here and Now: Poems

Feature > Poetry > Stephen Dunn

Blind Date With The Muse

Well, not exactly blind; I knew of her.

I was the needy unknown, worried

about appearance, and what, if anything,

she'd see beneath it. And, desperate

as this sounds, it was I who fixed myself up—

I didn't mind being middleman

to the man I longed to be. "Yes," she agreed,

then, "I hope you're not the jealous type."

I lied, and she named the time and place,

told me there'd be others, ever and always.

The door was open. And there we all were—

men and women, empty handed

and dressed down—each of us hoping

to please by voice, by tone. In her big chair

she welcomed or frowned, and one man

she gently touched, as if to say, "Don't

despair, it will be delivered soon."

Even as I hated him, I took heart.

She was the plainest woman I'd ever seen.

I wanted to make her up, but all arrangements

seemed hers—I found myself unable

to move. "You look lonely," she said,

"a little lost, the kind of man

who writes deathly poems about himself.

Sensitive, too," she added, and laughed.

Thus began the evening the Muse,

that life-long tease, first spoke to me.

"If you want to be any good

you must visit me every day," she said.

And then, "I'm hardly ever home."

I was the needy unknown, worried

about appearance, and what, if anything,

she'd see beneath it. And, desperate

as this sounds, it was I who fixed myself up—

I didn't mind being middleman

to the man I longed to be. "Yes," she agreed,

then, "I hope you're not the jealous type."

I lied, and she named the time and place,

told me there'd be others, ever and always.

The door was open. And there we all were—

men and women, empty handed

and dressed down—each of us hoping

to please by voice, by tone. In her big chair

she welcomed or frowned, and one man

she gently touched, as if to say, "Don't

despair, it will be delivered soon."

Even as I hated him, I took heart.

She was the plainest woman I'd ever seen.

I wanted to make her up, but all arrangements

seemed hers—I found myself unable

to move. "You look lonely," she said,

"a little lost, the kind of man

who writes deathly poems about himself.

Sensitive, too," she added, and laughed.

Thus began the evening the Muse,

that life-long tease, first spoke to me.

"If you want to be any good

you must visit me every day," she said.

And then, "I'm hardly ever home."

Here And Now

— for Barbara

There are wordsI've had to save myself from,

like My Lord and Blessed Mother,

words I said and never meant,

though I admit a part of me misses

the ornamental stateliness

of High Mass, that smell

of incense. Heaven did exist,

I discovered, but was reciprocal

and momentary, like lust

felt at exactly the same time—

two mortals, say, on a resilient bed,

making a small case for themselves.

You and I became the words

I'd say before I'd lay me down to sleep,

and again when I'd wake—wishful

words, no belief in them yet.

It seemed you'd been put on earth

to distract me

from what was doctrinal and dry.

Electricity may start things,

but if they're to last

I've come to understand

a steady, low-voltage hum

of affection

must be arrived at. How else to offset

the occasional slide

into neglect and ill-temper?

I learned, in time, to let heaven

go its mythy way, to never again

be a supplicant

of any single idea. For you and me

it's here and now from here on in.

Nothing can save us, nor do we wish

to be saved.

Let night come

with its austere grandeur,

ancient superstitions and fears.

It can do us no harm.

We'll put some music on,

open the curtains, let things darken

as they will.

To My Doppelganger

You were always the careful one,

who'd tiptoe into passion

and cut it in half with your mind.

I allowed you that, and went

happier, wilder ways. Now

every thought I've ever had

seems a rope knotted

to another rope, going back

in time. We're intertwined.

I've learned to hesitate

before even the most open door.

I don't know what you've learned.

But to go forward, I feel,

is to go together now. There's a place

I'd like to arrive by nightfall.

who'd tiptoe into passion

and cut it in half with your mind.

I allowed you that, and went

happier, wilder ways. Now

every thought I've ever had

seems a rope knotted

to another rope, going back

in time. We're intertwined.

I've learned to hesitate

before even the most open door.

I don't know what you've learned.

But to go forward, I feel,

is to go together now. There's a place

I'd like to arrive by nightfall.

Landscape And Soul

Though we should not speak about the soul,

that is, about things we don't know,

I'm sure mine sleeps the day long,

waiting to be jolted, even jilted awake,

preferably by joy, but sadness also comes

by surprise, and the soul sings its songs.

And because no one landscape compels me,

except the one that's always out of reach

(toward which, nightly, I go), I find myself

conjuring Breugel-like peasants cavorting

under a Magritte-like sky—a landscape

the soul, if fully awake, could love as its own.

But the soul is rumored to desire a room,

a chamber, really, in some far away outpost

of the heart. Landscape can be lonely and cold.

Be sweet to me, world.

that is, about things we don't know,

I'm sure mine sleeps the day long,

waiting to be jolted, even jilted awake,

preferably by joy, but sadness also comes

by surprise, and the soul sings its songs.

And because no one landscape compels me,

except the one that's always out of reach

(toward which, nightly, I go), I find myself

conjuring Breugel-like peasants cavorting

under a Magritte-like sky—a landscape

the soul, if fully awake, could love as its own.

But the soul is rumored to desire a room,

a chamber, really, in some far away outpost

of the heart. Landscape can be lonely and cold.

Be sweet to me, world.